A few years ago, art critic Peter Schjeldahl noted that “graphic novels…are to many in their teens and twenties what poetry once was, before bare words lost their cachet.” In other words, graphic novels—long-form comics—are what all the cool kids are reading. This claim, in and of itself, is hardly new or shocking, but what interests me is his use of the term “avant-garde” in reference to graphic novels, or, as he somewhat disparagingly comments, “pumped-up comics.” “Avant-gardes,” he asserts, “are always cults of difficulty,” before launching into a discussion of his first example, Jimmy Corrigan by Chris Ware. Coming from the field of arts criticism, it may seem self-evident to refer to experimental or “difficult” comics as avant-garde [1], but in comics criticism it’s not as obvious; more frequently, the cartoonists Schjedahl mentions (Art Spiegelman, Dan Clowes, Marjane Satrapi) are referred to as “alternative”—to differentiate them from the mainstream publishing houses such as DC and Marvel—rather than “avant-garde.” This distinction, however, raises even more questions: is the avant-garde part of mass culture, or is it inherently antagonistic to “bourgeois” art forms and institutions? Does the “avant-garde” imply a kind of rebellion, and, if so, is the nature of this revolt political, or is it more directed at renewing and reinventing art forms, or both? What are implications of using the term “avant-garde” for comics?

The military origins of the French term—referring to the troops who are first to clash with the opposing army on the front line—connote a violent confrontation. Early twentieth century European artistic movements such as Futurism, Surrealism, and Dadaism adopted the term to indicate a radical break with the past and a deliberate challenge to institutional art by blurring the line between art and life (Bürger 53; Calinescu 117). Unfamiliar, incomprehensible, or blatantly disturbing forms were intended to shock and offend the slumbering sensibilities of a complacent middle class. Now that artifacts from these historical “isms” are comfortably ensconced in the world’s finest museums, it’s a little hard to take this oppositional stance seriously when we reread avant-garde manifestos bristling with exclamation points and terse, grandiose declarations. Spanish cartoonist Max affectionately mocks this tradition in Bardín Superrealist (2007) when his character Bardín gets his friend Cirlot all riled up with his comics manifesto: “Wake up, oh cartoonists! Wake up from your Marvel-ous dreams! Create comics even though no one pays you for them, no one reads them! Cartooning is an art of virtue! Let us undermine the syntax of sense, the logic of profit!” (Cirlot eagerly responds “Yes! Hit the streets, comrades! Yes! Long Live Free Love,” before lapsing into embarrassed silence). The entire book, in fact, is an inspired contemporary homage to the tradition of surrealism with a mix of allusions to Un Chien Andalou, Henry Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare, and Mickey Mouse [2].

Quixotic as this manifesto-driven notion of the avant-garde may seem, it still holds power in a reinvented form by L’Association, a fiercely independent comics publisher based in Paris (see Bart Beaty’s Unpopular Culture for a thorough discussion of this phenomenon). Jean Christophe-Menu, the president of L’Association, lays out his vision of avant-garde comics while simultaneously attacking larger French comics publishers who he believes are coopting and corrupting this agenda with their commercial interests. In his essay manifesto Plates-bandes (2005), Menu unapologetically claims the term “avant-garde,” explaining how the work of Association cartoonists is a revolutionary alternative to the 48CC album model of mainstream comics publishers (popular 48 page hardbound color comics), and is rooted in Surrealist practices such as the exquisite corpse and dream stories. Oubapo, a subset of the most original and daring work in L’Association, is explicitly linked to the literary movement Oulipo, and is a dazzling example of experimentation with comics form. Like Oulipo, Oubapo plays with constraints—self-imposed rules of composition that produce surprising and creative results. To site just one example, Etienne Lecroart used the model of the literary palindrome—a line that can be read backwards and forwards—and created the comic-palindrome Le Cercle vicieux (2000), a story about a mad scientist and a time machine. As Bart Beaty has pointed out, this particular interpretation of the avant-garde rests on a sharp distinction between a notion of modernist “high culture” and popular versions of comics that L’Association wants to reject. Thus, for L’Association, “a comic book avant-garde is no longer a postmodern intersection of high and low, but an attempt to create comics in a modernist framework” (76). The formal difficulty of these works is an effort to engage with the modernist tradition of experimentation and innovation [3].

The tension between high and low culture is played out somewhat differently in American comics criticism, which is very evident in the varied uses of the term “avant-garde” in this context. For instance, in Hillary Chute’s recent book Graphic Women (2010), she simultaneously invokes artistic complexity and popularity without necessarily seeing a contradiction between the two: “Comics works can deliberately disrupt the surface texture of their own pages—often invoking aesthetic practices of the historical avant-garde—yet they model a post-avant-garde praxis in the very fact of their popular availability, in the ‘mass appeal’ of the medium” (Chute 11). Renée Silverman makes a similar claim in The Popular Avant-Garde when she argues that aesthetic and political dimensions of the avant-garde not only exist in popular culture, but “contribute enormously to the vanguard’s needful redefinition and reformulation” (Silverman 13). Thus, reading popular culture as avant-garde “upends the aesthetic hierarchies to which we have grown accustomed” (12). Bearing in mind this aesthetic agenda, it makes sense that two chapters of the book concern comics: the first is a political critique of Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers; the second is a study of Franciszka Themerson’s Ubu Comic Strip.

Considering the avant-garde as including (rather than excluding) popular culture is part of a larger trend in modernist studies, which has also increasingly turned to popular culture to broaden the scope of what falls under the definition of “modernism” [4]. Robert Scholes states that we should “rethink the Modernist canon and curriculum, opening up both of these to accommodate texts formerly excluded,” (4) adding that cartoons “may be ‘Low’ but they are clearly engaged in a dialogue with the ‘High,’ and we need to hear the entire dialogue if we want to understand what modernism was doing” (90). A survey of the influential journal Modernism/Modernity reveals that the concept of avant-garde has been extended to interpretations of mass culture in a variety of forms (dance, newspapers, radio programs, and other popular entertainments). In fact, the first article that analyzes comics—in this instance, Krazy Kat and Cat Woman—was just published in 2011 (“Cat People,” by Glenn Willmott).

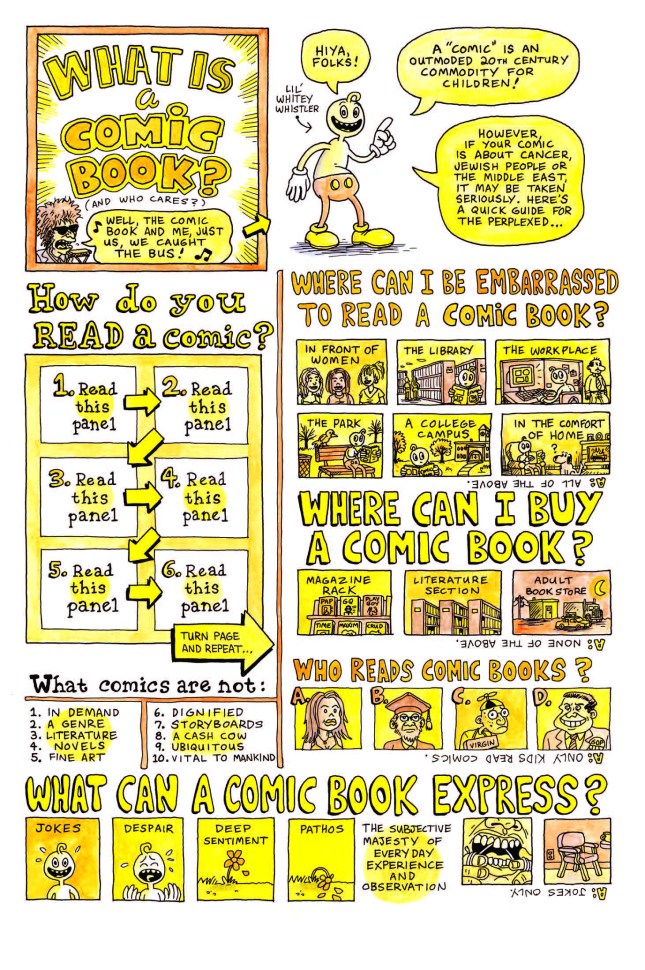

The problem, however, with eliding the popular and the avant-garde in the case of comics is that both critics and cartoonists still feel the lingering need to redress the medium’s history as a “low” or degraded form unworthy of scholarly attention [5]. As a consequence, the medium teeters between high and low, between respectability and kitsch. One example of this tension can be found in “What is a Comic?” (2008) by Nate Neal. A character in Mickey-Mouse pants defines the medium as “an outmoded 20th century commodity for children,” with the following proviso: “However, if your comic is about cancer, Jewish people or the Middle East, it may be taken seriously.” In this hierarchy, comics that address social and political topics are accepted, while the rest is relegated to juvenilia. But on the lower right, Neal’s list of “What Comics Are Not”—“in demand; a genre; literature; novels; fine art; dignified; storyboards; a cash cow; ubiquitous; or vital to mankind” — suggests that the whole enterprise is fraudulent. And yet this comic about comics is included in Fantagraphics journal Mome (now discontinued), a collection of artsy, challenging work that fits the definition of “avant-garde” from both an aesthetic and political perspective.

Returning to the case of Chris Ware, Peter Schjeldahl’s first example of “difficult” avant-garde comics, critics have noted how Ware’s work is deeply ambivalent towards the popular culture roots of the medium. On the dust jacket of McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern #13, a collection of contemporary alternative comics edited by Ware, he satirizes superhero comics in “Adolescent Power Fantasy Man,” a short strip only five panels long in which the main character swoops down, smashes a rock, and takes off again. His introduction includes another strip called “High Score” in which a character approaches Mr. Score with the following revelatory news: “Check it out…comics are now, like, a respected language, with an esthetic grounding all their own! See? They address topics like the Holocaust, spirituality, notions of identity and sex!” These optimistic pronouncements are, however, immediately undercut when Mr. Score complains that his friend has interrupted his Superman video game. And of course there’s Jimmy Corrigan, the eponymous and decidedly un-super anti-hero of Ware’s graphic novel, who is trying to discover who he is as he wanders around in his “Superman” t-shirt.

Daniel Worden argues that Ware’s work denigrates the commercial, mainstream versions of comics such as DC and Marvel by emphasizing “the artist’s singular vision as aesthetic essence” (907). Worden reproaches this tendency to distance comics from mass-produced forms, stating that it “reproduces some of the same prejudices as it did for modernism in the first half of the twentieth century” (907). Following Worden’s lead, Marc Singer makes a similar claim when he states that Ware’s emphasis on “realism” (by which he means “documentary journalism…psychological character study and self-revelation”) “perpetuate[s] traditional, arbitrary divisions between high and low culture even as he seeks to position comics between the two” (Singer 29). The problem with this, in his view, is that Ware is thus “sustain[ing] some of the hierarchies of literary and artistic value that have long marginalized comics.”

On the other hand, Ware’s modernist, avant-garde position could also be understood as a strategic, oppositional stance as the medium changes and evolves given that an interest in aesthetically complex comics “has come about precisely as graphic literature aspires to the status of literature as such” (Ball 106). Moreover, cartoonists such as Ware, Daniel Clowes, Charles Burns, and Seth are as influenced by Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s RAW magazine as they are by mass culture. A compilation of European and American comics artists published in the 1980s, RAW was never shy about flaunting its avant-garde pedigree with subtitles like “The graphix magazine that overestimates the taste of the American public,” or “the magazine for damned intellectuals.” In this respect, Ware and other contemporary cartoonists advance a vision of art comics that is not far from the anti-commercial avant-garde position of L’Association [6].

Where does this leave us if we want to think of comics in terms of the avant-garde? Not everything that is popular is avant-garde, and not everything that is avant-garde is popular. The avant-garde is a moving target, always defined in opposition (aesthetically, politically) from what came before. What is interesting about comics at this particular moment in time is that some of the most innovative contemporary cartoonists position themselves in terms of an avant-garde sensibility even as they simultaneously mock the very idea.

Works Cited

Ball, David M., “Comics Against Themselves: Chris Ware’s Graphic Narratives as Literature.” In The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts. Paul Williams and James Lyons, eds. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. 103-123.

Beaty, Bart. Unpopular Culture: Transforming the European Comic Book in the 1990s. Toronto: U P of Toronto, 2007.

Bürger, Peter. Theory of the Avant-Garde. Trans. Michael Shaw. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Calinescu, Matei. Five Faces of Modernity. Durham: Duke University Press, 1987.

Chute, Hillary. Graphic Women: Life Narrative & Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia, 2010.

Doherty, Brian. “Comics Tragedy: Is the Superhero Invulnerable?” The Best American Comics Criticism. Ben Schwartz, ed. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2010. 24-25.

Groensteen, Thierry. “Why Are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimation?” A Comic Studies Reader. Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester eds. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009. 3-12.

Kuhlman, Martha. “In the Comics Workshop: Chris Ware and Oubapo.” The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking. Martha B. Kuhlman and David M. Ball. eds. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. 78-89.

Max. Bardín the Superrealist. Trans. Kim Thompson. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2006.

Molotiu, Andrei. Abstract Comics. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books, 2009.

Neal, Nate. “What Are Comics?” Mome 12 (Fall 2008). np.

Scholes, Robert. Paradoxy of Modernism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Schjeldahl, Peter. “Words and Pictures: Graphic Novels Come of Age,” New Yorker, October 17, 2005, 162-68.

Silverman, Renée. “Introduction.” The Popular Avant-Garde. New York: Rodopi, 2010.

Singer, Marc. “The Limits of Realism: Alternative Comics and Middlebrow Aesthetics in the Comics of Chris Ware.” In The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking. Martha B. Kuhlman and David M. Ball. eds. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. 28-44.

Wertham, Fredric. Excerpt from Seduction of the Innocent. In A Comics Studies Reader. Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester eds. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009. 53-57.

Ware, Chris. “Adolescent Power Fantasy Man,” Strip. McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern 13. (2004): dust jacket.

————-. “High Score.” Strip. McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern 13. (2004).

Willmott, Glenn. “Cat People.” Modernism/Modernity 17:4 (2011): 839-856.

Worden, Daniel. “The Shameful Art: McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Comics, and the Politics of Affect.” Modern Fiction Studies 52:4 (2006): 891-917.

Martha Kuhlman is Associate Professor of Comparative Literature in the Department of English and Cultural Studies at Bryant University where she teaches courses on the graphic novel, Central European literature, and critical theory. She coedited The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking with the University Press of Mississippi (2010) with Dave Ball of Dickinson College. In addition, she has published articles on comics in The Journal of Popular Culture, European Comic Art, the International Journal of Comic Art, and contributed to the MLA volume Approaches to Teaching the Graphic Narrative.

[1] Andre Molotiu uses the term in his introduction to Abstract Comics, an international collection of work that “chronicles the recent flourishing of the genre, most likely mediated by the rise of the internet, which has made possible an avant-garde community spread across the surface of the globe…” (Molotiu 3).

[2] Max and the Italian cartoonist Igort (Five is the Perfect Number, Baobab) discussed their debt to avant-garde European movements in a presentation titled “Graphic Novels from Europe” held at the Museum of Comic Art in New York City, Nov. 20, 2008.

[3] Although the French members of Oubapo are no longer producing issues of their journal Oupus, American cartoonist Matt Madden is reviving an interest in this type of experimentation with constraints and collecting examples internationally through his Oubapo Facebook group (95 members and counting).

[4] Calinescu criticizes the tendency of American critics to conflate the avant-garde with modernism, although he does see both terms as connoting negation. He understands the avant-garde as a parody of modernism, rather than as equivalent to modernism (140-141).

[5] For an international overview of the history of comics as a degraded form, see “Why Are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimization?” by Thierry Groensteen. In the American context, regarding comics as “trashy” literature is connected to the history of Fredric Wertham’s work, Seduction of the Innocent, which claimed that comic books had a deleterious effect on children (for an excerpt, see the entry in A Comic Studies Reader). There is also the view that mainstream comics are only the product of a system in which individual artists have little control and corporate greed dictates content. For example, Brian Doherty notes, “critics, when they deigned to notice comics at all, dismissed [mainstream superhero comics] as junk…” an attitude, he continues, which has “barely changed” in the present (25).

[6] For a more extensive explanation of my claim that Spiegelman, Ware, and Oubapo are positing an “avant-garde” notion of comics, please see my chapter “In the Comics Workshop: Ware and Oubapo” in The Comics of Chris Ware.

charleshatfield

2012/08/10 at 15:29

Martha, thanks for this fascinating look at a still-divisive subject!

I’m often struck these days by the confusions that result whenever we seek to explain comics’ development by analogy or connection to the narrative of some past artistic Ism. The question of Modernism is a case in point. Yet we cannot simply dismiss these analogies, because comics creators are mindful of them too!

LikeLike

MK

2012/08/12 at 19:49

Yes, it is divisive, isn’t it? I’m glad that at least I’ve generated some discussion. The article attempts to show how the term “avant-garde” is already being used in academic discourse to show some discontinuities and differences.

LikeLike

madinkbeard

2012/08/11 at 20:04

Correction: Menu is now former-President of L’Association.

I found the search for an avant-garde in works that are pretty much a mainstream part of comics really odd. The avant-garde is a moving target and it has moved past Ware who is hardly that “difficult” and pretty much defines one end of the mainstream conception of comics. His embrace by the art world also seems to negate him as avant-garde (see Bart Beaty’s new Comics Versus Art for a good look at Ware and the artworld)… I guess I’ll have to go look up your article in the Ware book…

Similarly, in comparison with a lot of less known work out there it is really hard to see Mome as aesthetically or politically avant-garde. If anything it was disappointingly staid in its conception of what comics could be (with some few exceptions like some of Anders Nilsen’s work). This reads like another case of someone writing about comics who is completely missing the work that should be considered as the avant-garde of comics, which aren’t being published by the likes of Pantheon or Fantagraphics. There are a lot of forward looking cmics out there that, at least aesthetically, might fit some conception of an avant-garde. And certainly the web/mini-comics are more in tune institutionally with the avant-garde.

LikeLike

MK

2012/08/12 at 19:46

Thanks for your reply. My examples–MAx (Bardín the Superrealist), Nate Neal, and Chris Ware don’t really strike me as mainstream, but that probably needs to be defined. Ware is, I grant you, commercially successful, but I don’t think his work is particularly easy to decipher. After spending two years of quality time looking at his compositions, I would say that they are an amazing example of the merits of “close reading.” The more I looked and studied, the more I found.

I also disagree about Mome, but it would take me a little time to get back to you with examples. I often use work from Mome to illustrate experiments in narrative when I teach my graphic novel course. Kramer’s Ergot, of course, also comes to mind, but the listings in the article were not meant to be exhaustive. It made sense to me to cite works that were probably (or possibly) familiar to readers.

I’m actually working on another project that takes a much finer-grained look at alternative comics in the context of the Providence arts scene. That paper will include hand-made minicomics and comics in a number of formats. I’d welcome your examples of other comics that you would consider ground-breaking from an aesthetic perspective. Given that you review comics, you have a more comprehensive overview than the average reader.

LikeLike

MK

2012/08/12 at 21:07

Also–the point about Beaty’s new book Comics vs. Art is well-taken. It’s only been out for a month, however, and I haven’t had the chance to read it yet.

LikeLike

Beth Davies-Stofka

2012/08/12 at 15:14

“But on the lower right, Neil’s list of “What Comics Are Not”—“in demand; a genre; literature; novels; fine art; dignified; storyboards; a cash cow; ubiquitous; or vital to mankind” — suggests that the whole enterprise is fraudulent.”

LOL! I love that. It’s very functional, keeping the act of creating a comic safe from the temptations of the big head. “I am a fraud” is an excellent personal mantra. It’s the subtext behind every single great comic.

It seems that this essay is really just an exploration of whether or not comics, especially “alternative” comics, should be considered “avant-garde.” In other words, it feels like an exercise in defining and classifying. That’s a valid activity! Why not write a response to Schjedahl? It needed doing. But trying to define and classify comics falls apart in this case because there are too many dependencies. Our definitions always depend on which comics are read, or even noticed (see madinkbeard’s reply), and also on how one defines “avant-garde.” In addition, generating definitions of “the avant-garde” is somewhat counter to the political spirit of “avant-garde.” To be the advance shock force, we must do violence to definitions. “I am a fraud” is again an excellent mantra when working and thinking on the front lines, or in enemy terrain.

I don’t know if there are any avant-garde projects of the present, not in terms of the political intent, or really, the reach, of Futurists, Surrealists, or Dadaists. That’s something worth exploring! “The avant-garde is a moving target, always defined in opposition (aesthetically, politically) from what came before.” I agree that it is a moving target, but I don’t think it’s avant-garde unless it is defined in opposition (aesthetically, politically) *to what is*.

LikeLike

MK

2012/08/12 at 19:35

Thanks for your reply. One of my primary aims is to survey recent scholarship on comics (most references are from 2010+) and see how the term was used in order to raise some questions. Is the term mainly used aesthetically, in politically, or both? What kind of work gets called “avant-garde” and why? What are the stakes of this designation? There’s actually quite a lot of confusion about this. But as you say in your conclusion, I think the term “avant-garde” can be usefully applied to works that consciously seek to break with prior tradition. My other main point is to show the difference between European and American understandings of the term. I would say that both Max and Igort are in fact influenced by the Surrealist, Futurist, and Dada movements (check them out). This is what Max said, in effect, when I saw him speak at Mocca in 2008.

LikeLike

JW

2012/08/13 at 02:02

If you were to consistently bet that any comic, including those yet to be created, that purports (or is purported) to be avant garde is in fact (or could be argued to be) distressingly mainstream, you would not lose money. I bet.

LikeLike

JTr

2012/08/16 at 13:05

Interchange ‘comic’ with ‘piece of art’ (or literature or music) in your statement and this will make the same sense or nonsense. This discussion gets meaningless if we don’t define our respective uses of avant-garde, alternative and mainstream, and even give examples or counter-examples for these categories.

IMO, ‘mainstream’ looses its meaning if we don’t look at sales figures, predominant cultural understanding of comics etc., and make a difference according to these criteria.

Only because of some leading journalists and some academics have appreciated Ware, Clowes and the like, they can’t be called mainstream. At some time in their careers, they were certainly avant-garde.

Everyone respects Kandinsky, Joyce, or Schönberg, but calling them mainstream because of this? Cf. Lessing as early as 1771: “Wer wird nicht einen Klopstock loben? / Doch wird ihn jeder lesen? – Nein. / Wir wollen weniger erhoben / Und fleissiger gelesen sein!” (Who would not praise some Klopstock? But will everyone read him? – No. We want less to be applauded, but more eagerly be read!)

For me that shows the difference between mainstream and not mainstream.

Joachim

LikeLike