Vertigo, DC’s adult-oriented imprint, has been repeatedly praised for having ‘fully joined the fight for adult readers’ in the early 1990s (Weiner 2010: 10). It has been noted that this “fight” coincided with the imprint’s ‘adoption of the graphic novel format’ as well as ‘a new self-awareness and literary style’ which ‘brought the scope and structure of the Vertigo comics closer to the notion of literary text’ (Round 2010: 22). However, little attention has been devoted to the very cultural identity of the imprint, even if Vertigo has since its early days engaged in an intro- and retrospective discourse on the American comics form, its history, and the power relations inherent to its industry. This short essay intends to start filling that gap by investigating Vertigo’s archival impulse. It argues that in deploying various rewriting strategies which engage with specific past (comics) traditions, the label has activated a unique memorious discourse that provides a self-reflexive and critical commentary on the structuring forces of the American comics field, its politics of domination and exclusion, and hence its canons.

Inter- and hypertextuality have been central to Vertigo’s cultural identity since its debut. The titles that launched the imprint in the early 1990s (Animal Man, Doom Patrol, Hellblazer, Sandman, Shade the Changing Man, and Swamp Thing), for example, are all reinterpretations of earlier horror and supernatural titles from the DC universe. Of course, the common “reinvention” denominator that characterizes this cluster of titles and the early years of the imprint did not take place in a vacuum. Many comics had paved the way for this before the creation of the imprint in 1993. Alternative comics from the 1980s such as Love and Rockets and The Rocketeer, for instance, were very influential re-imagined sci-fi comics. Superhero texts such as Watchmen (1986-1987) and The Dark Knight Returns (1986) also engaged in genre revision and, in so doing, problematized issues of continuity as well as complicated the mythology of long-running series and/or characters (cf. Klock 2002). However, as Round (2010) has argued, proto and early Vertigo comics differed from revisionist superhero titles of the 1980s and their “grim and gritty style.” The titles that launched the label were ‘reconceived […] not simply as “more realistic” superheroics,’ but instead as texts offering ‘mythological, surreal, religious, and metafictional commentaries on the comics medium and industry’ (Round 2010: 16). Round maintains in fact that these early Vertigo series ‘absorbed and subsumed their previous [DC] incarnations’ (2013: 327) and that therefore ‘[t]he notion behind Vertigo was one of redefinition’ (ibid.).

I couldn’t agree more. However, I wish to point out that because all of these early Vertigo comics revolve around what I prefer to describe as “rewriting” [1] insofar as they dislocate characters from their original contexts and rearticulate them into new ones that notably explore horror and the occult as well as mix self-reflexivity with generic subversion, they brought coherence and credibility to the label’s editorial project. The fact that the Vertigo label was retro-actively applied to, for example, texts such as Alan Moore et al.’s Swamp Thing (1984-1987) and the first 46 issues of Sandman (1989-1993) is not innocent since these series carried the seeds that would later establish the cultural identity of the imprint, namely subversive rewriting strategies, metafictional elements, and an illogic of fantastic and uncanny worlds semantics. In fact, taken together, the early Vertigo titles’ obsession with specific past (comics) traditions and the de- and/or reconstruction of these traditions founded the label’s poetics of demarcation through a particular politics of commemoration. Although sharing some similarities with the movement of revisionist superhero narratives, this politics of commemoration highlights the imprint’s willingness to engage with inter- and hypertextual strategies beyond the superhero genre. Since its debut, the label has indeed combined its revisiting of the DC archive with a fascination for the heritage of the pulps and the cherishing of Gothic tropes and motifs, a polymorphous (postmodernist) rewriting ethos that still animates the cultural identity of the label today.

Vertigo’s revisiting of the DC archive, for instance, can be seen in the imprint’s reinterpretations of the House of Mystery (2010-2011) and House of Secrets (1996-1998) DC anthologies, its reprises of old series and/or characters (Unknown Soldier (1997, 2008-2011), Haunted Tank (2009), Uncle Sam (1997), as well as the series of titles published under the sub-imprint “Vertigo Visions” (1993-1998)), or else in the satire of the war comics Our Army at War in Rick Veitch’s Army@Love (2007-2008). The label also clearly reclaims the cultural heritage of the pulps with its strong focus on popular genres. Serial narratives such as Sandman Mystery Theatre (1993-1999), 100 Bullets (1999-2009), and Scalped (2007-2012), the whole “Vertigo Crime” sub-imprint (2009-2011), and the collections of short graphic stories Strange Adventures (2011) and Time Warp (2013) clearly resonate thematically or otherwise with many successful pulp genres such as science fiction and crime stories, as well as with pulp magazines such as Amazing Stories, Marvel Tales, and Spicy Detective.[2] Finally, the imprint’s fascination for terror and horror stories can be observed in numerous titles such as Sandman (1989-1996) and its many spin-offs, In the Shadow of Edgar Allan Poe (2003), Industrial Gothic (1995-1996) and The House on the Borderland (2004) which is adapted from William Hope Hodgson’s 1908 eponymous supernatural horror novel. More specifically, these Vertigo texts and others articulate many of the dominant features of Gothic fiction such as the fragmentation of identity, the blurring of the boundaries between fiction and reality, the interplay between the supernatural and the metafictional, and finally the presence of ghosts and doppelgängers.

As suggested earlier, the implications of these rewriting strategies and the archival impulse behind them should not be underestimated. As Henry Jenkins reminds us in a recent essay exploring the archival, the residual, and the ephemeral in Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (2004): ‘collections and stories are both ways of managing memory’ (2013: 303). Therefore, according to Jenkins, processes ‘(re)performing this memory work’ (ibid.) should not and ‘cannot be separated from […] the formation of canons of comics’ (2013: 302). In other words, Vertigo’s rewriting and archival ethos functions as a memorious discourse, a discourse that is able to disrupt the canon-formation practices that permeate the structuring forces of the American comics field. And in distancing itself from the mnemonic and residual strategies adopted by the mainstream and alternative poles of the industry,[3] Vertigo has adopted a subversive middle-ground position in regards to the mainstream/alternative dialectic.[4]

For example, Vertigo revisions of older DC material – including the revisiting of less popular, second-class, or long-forgotten characters and/or series – draw attention to the heritage of mainstream comics beyond the superhero genre. In fact, Vertigo’s’ “archaeological excavation” of previous DC texts that do not belong to the superhero tradition or ambiguously refer to the superhero can be said to function as a specific effort of patrimonialization, one that “writes back” to the canon-making practices of the mainstream industry which, quite unsurprisingly, has relied on its most enduring genre to engage with the history and memory of its publishing lines but, in so doing, has strongly overshadowed other comics traditions and other possible narrative worlds. It is true that this “excavation” has very much depended on the artists’ knowledge of these past comics – which were the ones they read in their youth – and that, therefore, a certain superheroic nostalgia inevitably permeates the comics of Moore, Gaiman, and other early Vertigo writers usually associated with the so-called “British invasion.” Nevertheless, the nostalgic approach of these artists has always been an informed, critical, and self-reflexive one which called into question some of the dominant generic codes of the industry, particularly that of superheroics.

In a similar fashion, the imprint’s fascination with the pulp tradition not only illustrates how Vertigo distances itself from the mainstream press, it also challenges the sometimes elitist and difficult tone and aesthetics of the alternative pole of the industry. The label implicitly mocks, it seems, the alternative artists and editors’ rejection of genre-based comics, and more generally, the denigrating discourse held against pulp fiction and comics.[5] Moreover, in embracing the pulp tradition, Vertigo seeks other allegiances than the ones developed by alternative artists such as Chris Ware and Art Spiegelman who regularly pay homage to early 20th century comics, including Krazy Kat, The Katzenjammer Kids, and Little Nemo in Slumberland. It is true that although they most likely attracted different audiences, both early 20th century strips as well as pulp magazines were deeply commercial and popular. Nevertheless, alternative artists’ recurrent invoking of early 20th century strips is very specific. More often than not, alternative artists focus on the themes of rêverie and (self-)reflexivity that were central to these past cartoonists’ works. Additionally, in recurrently drawing our attention to some of the structuring units of the comics form (panels, pages, strips) as well as in comparing and/or connecting architecture to and with the fragmented nature of comics and (traumatic) memory,[6] alternative artists pay tribute to how early 20th century cartoonists inventively played with moment-to-moment transitions, geometric plotting, and what Scott Bukatman describes as the ‘mapping of spatio-temporal illogic’ in discussing Krazy Kat (2012: 45, italics in the original). In contrast, Vertigo comics’ intertextual engaging with the pulp tradition revolves around the exploring of genre boundaries, “cheap thrills,” and provocative as well as exploitative storytelling techniques. Thus, at the risk of generalizing, whereas alternative artists ‘aim at giving their works,’ as Jeet Heer puts it in discussing Chris Ware’s comics, ‘a pedigree and lineage’ that is arguably rooted in formal experimentation and aesthetic innovation (2010: 4), in focusing on violence and in re-exploring crime- as well as sci-fi-related contents with self-reflexive twists, Vertigo comics not only acknowledge the populist and sensational origins of comic books, but also ironically play with and comment on the “low-brow” status marker that is often associated with the pulp tradition. Arguably, Vertigo’s cherishing of pulp themes and aesthetics may also be read as a reaction against alternative comics’ ‘dominant narrative modes,’ i.e. ‘tragedy, farce, and picaresque’ (Hatfield 2005: 111), and how in favoring these modes, the alternative pole of the industry may have emphasized its elitist and highbrow tone and aesthetics, thereby ‘sustain[ing] some of the hierarchies of literary and artistic value that have long marginalized comics,’ as Marc Singer puts it analyzing Ware’s oeuvre (2010: 29).

Finally, Vertigo’s Gothic inclinations also participate in the label’s specific logic of commemoration and attendant politics of demarcation in regards to the mainstream/alternative dichotomy. After all, the politics of canon-making, according to Harold Bloom, imply ‘strangeness [and] uncanny startlement rather than a fulfillment of expectations’ (1994: 3). Vertigo’s de- and reconstructionist take on many popular genres as illustrated in titles such as Animal Man, Flex Mentallo (1996), and Fables (2002-) certainly echoes the idea of transgression that is so characteristic of the Gothic. So too does the thematization of monstrous excesses, masking, and the carnivalesque in narratives such as Preacher (1995-2000) and Enigma (1993). The ‘spectral trope of haunting’ so characteristic of the Gothic, Round contends (2012: 336), is also reminiscent of the strategy of ‘retconning’ at work in titles such as Sandman and Swamp Thing (2012: 338). She defines retconning as ‘retroactive continuity, whereby past events are expunged or characters’ parameters reformulated’ (ibid.). More generally, however, her argument speaks to how countless Vertigo texts – be they inspired from older DC material, pulp fiction, and/or other traditions – are haunted by “ghostly visitations.” In other words, many Vertigo comics operate as “counterfictions” that oddly transform the idea of Gothic enclosure, i.e. the haunted house. Moreover, the multi-path and branching plots narrative strategies that Vertigo series such as Jack of Fables (2006-2011), The Unwritten (2009-), and Air (2008-2010) articulate find echo with the recurrent use of sinuous and cryptic settings such as labyrinths, catacombs and castles in Gothic fiction. More specifically perhaps, the sometimes complex and multi-layered rewriting strategies that these series and other Vertigo comics activate can be said to function as “(inter)textual ruins” that metaphorically resonate with the Gothic’s cherishing of maze-like, decaying, and/or devastated settings and locales. Following that logic, it should come as no surprise that the protagonists of Jack of Fables, The Unwritten, and Air find themselves lost or trapped in unknown countries and/or forgotten territories, “other” narrative dimensions, and/or alternate (literary) realities. Thus, the logic of possible worlds that characterizes these and countless other Vertigo comics is reminiscent of the ways in which Gothic texts metaphorically explore the boundaries between the real and the fantastic on the one hand, and of how the Gothic generally evokes the transgression of a unique, coherent, and self-contained reality on the other. In short, these and many other Vertigo comics epitomize a form of postmodernist ontological instability that presents itself, as Brian McHale would have it, as ‘an anarchic landscape of [fictional and textual] worlds in the plural’ (1987: 37).

Last but not least, historically speaking, Vertigo’s redeployment of Gothic tropes and themes also seems to directly resonate with the cherishing of zombies and other monsters of the ill-fated company of the 1950s: EC Comics. And in paying homage to EC while promoting what one might describe as “the return of the repressed,” Vertigo implicitly criticizes the censorship initiated by the Comics Code and, a fortiori, how mainstream comics became the “victims” of their own normative imprisonment.

Against the background of these observations, it is possible to argue that the label may well have revived the Gothic tradition in comics to highlight how, according to David Punter (1996), the Gothic develops itself in response to social trauma – read here not only the cultural stigma that genre-based comics creators, fans, and readers have suffered from, but also the ways in which both the mainstream and alternative spheres of the American comics field may have reductively formatted the industry, or at least, consolidated the agendas characterizing both ends of its spectrum. To put it somewhat differently, Vertigo’s cherishing of Gothic themes may be read as a kind of “testimonial literature,” one that makes use of ghosts, monsters, and uncanny storyworlds to ironically expurgate the demons haunting some of the past and possibly traumatic ‘“symbolic handicaps” that have contributed to the devaluation of comics as a cultural form’ (Beaty 2012, 19).

By way of conclusion, one could certainly evoke how Vertigo’s poetics of rewriting and politics of commemoration challenge Thierry Groensteen’s claim that comics is an ‘art without memory,’ an art that ‘gladly cultivates amnesia’ (2006: 67, my translation). It is in fact both surprising and interesting to note that Vertigo’s rewriting ethos seems to perfectly embrace Spiegelman’s archive-minded understanding of comics. The alternative artist and editor has indeed claimed – when asked in Angoulême last year to provide his short history of the comics form – ‘the future of comics is in the past’ (Spiegelman 2012, video). Obviously though, not any past. In recurrently paying homage to the DC archive beyond the superhero, the pulp tradition, as well as Gothic fiction, Vertigo has refashioned a certain historical and canonical matrix of comics which self-reflexively engages with the shifts in the meanings of cultural hierarchies both within and outside what Bart Beaty, drawing on the work of Howard S. Becker, has called ‘a comics world’ (2012: 8).

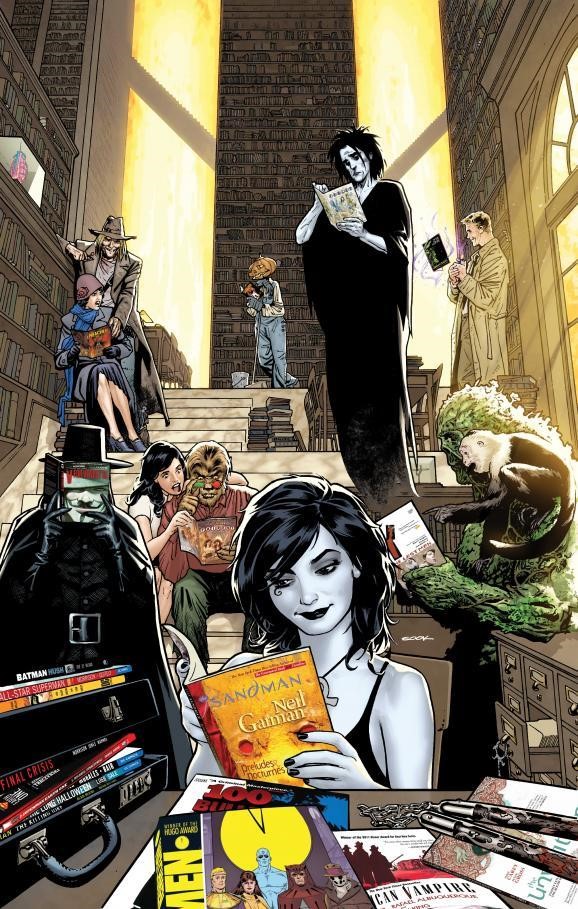

In having developed this specific memorious discourse for over 20 years, however, one might wonder if Vertigo has not commodified the strategies of rewriting that are part and parcel of its cultural identity. In adopting an ambiguous middle-ground position in regards to the mainstream/alternative dialectic, Vertigo has in effect very much developed an endogenous-spirited mind. The label’s logic of commemoration has indeed been closing in on itself, as is exemplified in the recent cover for the anthology Vertigo Essentials (2013) reproduced below. This cover portrays several popular characters from well-known Vertigo series gathered in a library – the archival space par excellence – and reading either the works they feature in or other famous works published under the Vertigo banner. Thus, although the label may have attempted to ‘redefine’ the medium (cf. Round 2010) in constructing its own canon – thereby both corroborating and sustaining the idea that ‘comics cannot be legitimated in the absence of canonical works’ (Beaty 2012: 9) – it has done so in a very subjective fashion. In other words, Vertigo’s archival impulse can be read as a specific memorious discourse, but one that contains criticism within a set of prescribed paradigms that reproduce some of the same prejudices that the label seems so keen to call into question and subvert.

Ryan Sook’s cover for the anthology Vertigo Essentials, 2013. ™ and © DC Comics. Used with permission.

Works Cited

Beaty, Bart. Comics vs. Art. Buffalo, London, and Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

Bloom, Harold. The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. London, New York, and San Diego: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1994.

Bukatman, Scott. The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2012.

Dony, Christophe. “Reassessing the Mainstream vs. Alternative/Independent Dichotomy, or, the Double Awareness of the Vertigo Imprint.” In Christophe Dony, Tanguy Habrand, and Gert Meesters (eds.). La Bande Dessinée en Dissidence: Alternative, Indépendance, Auto-édition / Comics in Dissent: Alternative, Independence, Self-Publishing. Liège : Presses Universitaires de Liège, forthcoming.

Dony, Christophe and Caroline Van Linthout. “Comics, Trauma, and Cultural Memory(ies) of 9/11.” In Joyce Goggin and Dan Hassler-Forest (eds.). The Rise and Reason of Comics and Graphic Literature: Critical Essays on the Form. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010. 178-187.

Dony Christophe, Tanguy Habrand, and Gert Meesters (eds.). La Bande Dessinée en Dissidence: Alternative, Indépendance, Auto-édition / Comics in Dissent: Alternative, Independence, Self-Publishing. Liège : Presses Universitaires de Liège, forthcoming.

Groensteen, Thierry. La Bande Dessinée: Un Object Culturel Non Identifié. Angoulême: Éditions de l’An2, 2006.

Hatfield, Charles. Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Heer, Jeet. “Inventing Cartooning Ancestors: Ware and the Comics Canon.” In David M. Ball and Martha Kuhlman (eds.). The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. 3-13.

Jenkins, Henry. “Archival, Ephemeral, and Residual: The functions of Early Comics in Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers.” In Daniel Stein and Jan-Noël Thon (eds.). From Comics Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 301-324.

Klock, Geoffrey. How to Read Superhero Comics and Why. New York: Pantheon, 2002.

McHale, Brian. Postmodernist Fiction. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

Punter, David. The Literature of Terror: A History of Gothic Fictions from 1765 to the Present Day. 2nd ed. Harlow: Longman, 2010 [1996].

Round, Julia. “‘Is this a Book?’ DC Vertigo and the Redefinition of Comics in the 1990s.” In Paul Williams and James Lyons (eds.). The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. 14-30.

—. “Gothic and the Graphic Novel.” In David Punter (ed.). A New Companion to the Gothic. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2012. 335-349.

—. “Anglo-American Graphic Narrative.” In Daniel Stein and Jan-Noël Thon (eds.). From Comics Strips to Graphic Novels: Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2013. 325-346.

Singer, Marc. “The Limits of Realism: Alternative Comics and Middlebrow Aesthetics in the Anthologies of Chris Ware.” In David M. Ball and Martha Kuhlman (eds.). The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2010. 28-44.

—. Grant Morrison: Combining the Worlds of Contemporary Comics. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

Smith, Erin A. “Pulp Sensations.” In David Glover and Scott McCracken (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Popular Fiction. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 141-158

Spiegelman, Art. “Une histoire personnelle de la bande dessinée.” Le Musée privé d’Art Spiegelman, Angoulême: CIBDI. October 25th, 2012. [Accessed on March 2nd, 2013]. URL <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PRIASI8PAD0&list=PLJWCjsENkVUzDAjJCIefndyJgDpA7OLQu&index=1>.

Christophe Dony is conducting doctoral research on the functions of inter- and hypertextuality in American comics at the University of Liège, Belgium. He is a member of ACME – an interdisciplinary research group dedicated to comics scholarship – with which he has contributed to the volume L’Association: Une utopie éditoriale et esthétique (Les Impressions Nouvelles, 2011). He recently co-edited Comics in Dissent: Alternative, Independence, Self-Publishing (Presses Universitaires de Liège, forthcoming) and Portraying 9/11: Essays on Representations in Comics, Literature, Films and Theatre (McFarland, 2011). His articles have notably appeared in The International Journal of Comic Art, The Comics Grid, and Studies in Comics.

[1] – Applying the term ‘rewriting’ to an art form with a strong visual component has its limits. Nevertheless, as I am primarily interested in the literary ramifications and intertextual influences pervading the poetics and politics of the imprint, I saw it fit to stick to the term. Moreover, it should be pointed out that a majority of Vertigo titles are scriptwriter-driven and/or are often borne from a writer pitching a story to the editorial staff of Vertigo – the artwork thus being often relegated in second position in the industrial process. This being said, by no means do I contend that Vertigo titles do not allude to, refer to, or quote other works visually. In fact, I would encourage scholars to carry out research examining the ‘aesthetic kinship’ or ‘iconographic genealogy’ permeating the visual styles of Vertigo artists.

[2] – The titles of these collections of graphic short stories also engage with DC’s back catalogue. Strange Adventures was the title of DC’s first science-fiction series which started in the 1950s. Likewise, Time Warp was a short-lived mini-series published by DC between 1979 and 1980.

[3] – For a critical exploration of the highly connoted terms “mainstream” and “alternative” and how their use and implications vary across both time and space in specific comics markets and fields, see Comics in Dissent: Alternative, Independence, Self-Publishing (Dony, Habrand, and Meesters, forthcoming).

[4] – As Marc Singer has observed in discussing the works of Grant Morrison, Vertigo ‘[has] sought to occupy the space between superheroes and alternative comics’ (2012: 21). The label, Singer contends, has ‘carve[d] out [an] interstitial market […] within the comics industry,’ a market ‘that fell between younger and older readers, new and familiar genres, mainstream content and independent creative practices’ (2012: 27, emphasis added). For a fuller discussion of the hybrid identity of Vertigo in regards to the mainstream/alternative dialectic, see Dony, forthcoming.

[5] – It has indeed been well recorded that the pulps of the early 20th century, as well as the dime novels of the late 19th century from which they developed, were ‘banned from public libraries, scorned by respectable periodicals, and widely held to feature stories that were commodities rather than works of art’ (Erin Smith 2012: 145). Unsurprisingly, similar charges have been pressed against the comics form during most of the 20th century: comics have been criticized for their lack of cultural relevance and aesthetic creativity.

[6] – The parallels between the fragmented construction of a comics page/work and architecture is most visible in Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers and, quite unequivocally, in Ware’s Building Stories. For more insights on the possible correspondences between the breakdown of the comics page/work and the structure of (traumatic) memory and how both re-collect and re-member fragments, see Dony and Van Linthout (2010).

Tim Pilcher

2013/10/26 at 14:02

Interesting article. Not sure I agree with it’s entirety, as everything we did out of the Vertigo UK office was the antithesis of what is postulated here (i.e. re-using back catalogue material and/or re-examining Pulp and comic tropes).

How does Rogan Gosh, 20/20 Visions, Kill Your Boyfriend, Sebastian O, Face, Tainted, etc. fit into this theory? Our remit was to produce original, creator-owned, one-off titles and miniseries. Most of the work that informed Grant Morrison and Peter Milligan’s writing at this time was far from comics.

Flex Mentallo was one of the rare occasions where we took a character from an existing title (Doom Patrol). Admittedly, you could easily postulate that pretty much everything Vertigo did had a gothic tinge to it. But I always felt that the imprint was far too diverse to be easily labelled like this (which is both a strength and a weakness). As I say in my forthcoming memoir, Comic Book Babylon:

“What Vertigo actually was, and what it stood for, was always a bit of an enigma. The one question I was asked more than any other, by aspiring creatives, was “What sort of stories and material are you looking for?” and the completely unhelpful reply was always “We’ll know it when we see it.” But the truth was that we didn’t want to pigeonhole ourselves to one genre or theme. We often joked that each story was “blah blah blah, but with a Vertigo twist” which was equally ambiguous. We had stories about superheroes, weird psychedelic tales, conspiracy adventures, horror, sci-fi. It really didn’t matter, provided the content was quality and challenging to both the reader and the medium.”

More info here: https://www.facebook.com/ComicBookBabylonKickstarter

Here endeth the crass commercial plug.

Tim.

LikeLike

Christophe Dony

2013/10/27 at 08:22

Hi Tim,

Thanks for your comment. It’s always nice to get some former insider’s knowledge.

Obviously, the categories of rewriting that I have outlined in the article are far from being exhaustive and do not represent the entirety of Vertigo’s identity and catalogue. The examples you mention may in effect not “fit” into the categories I have described. And this is possibly due to the fact that most of them were published in the early years of the imprint under specific circumstances. Sebastian O was a project inherited from the collapse of Disney’s imprint Touchmark Comics, Rogan Gosh was first published by 2000AD, and most of the other titles were part of the Vertigo Voices’ project which aimed at promoting creator-owned material – a “side project” of Vertigo, so to speak, which retrospectively, I think, was meant to respond to the increasing success of “alternative comics” on the one hand, and simultaneously expand Vertigo’s output and credibility as a label…

You’re right when you claim that Vertigo cannot be reduced to specific genres or themes. I have argued elsewhere in fact that the imprint continually lives up to its very name in articulating ambiguous and “vertiginous” relations with a wide array of traditions which include, but are not limited to, the Gothic, pulp fiction, and/or DC’s back catalogue.

This being said, I believe it makes sense to argue that Vertigo has developed a rewriting ethos which, since its early years, has taken many guises and shapes. Recent examples corroborating the idea that the imprint still plays with this trope of rewriting would include Brian Wood et al.’s revisiting of sagas in Northlanders or Ronald Wimberly’s Prince of Cats ( a “hip hop retelling” of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet that focuses on Tybalt). In short, while far from neglecting their influence, I’m trying to go beyond the celebrating of the early years and titles of the imprint. Rather, my aim is to look at the ways in which Vertigo developed a coherent while yet sometimes ambiguous editiorial project over the years – a project that I believe cannot only be reduced to the eccentric character, edgy, and possibly drug-enhanced titles of the early 1990s.

LikeLike

chdony

2013/10/27 at 08:26

Hi Tim,

Thanks for your comments. It’s always nice to get some former insider’s knowledge.

Obviously, the categories of rewriting that I have outlined in the article are far from being exhaustive and do not represent the entirety of Vertigo’s identity and catalogue. The examples you mention may in effect not “fit” into the categories I have described. And this is possibly due to the fact that most of them were published in the early years of the imprint under specific circumstances. Sebastian O was a project inherited from the collapse of Disney’s imprint Touchmark Comics, Rogan Gosh was first published by 2000AD, and most of the other titles were part of the “Vertigo Voices” project which aimed at promoting creator-owned material – a “side project” of Vertigo so to speak which retrospectively, I think, was meant to respond to the increasing success of “alternative comics” on the one hand, and simultaneously expand Vertigo’s output and credibility as a label on the other…

You’re right when you claim that Vertigo cannot be reduced to specific genres or themes. I have argued elsewhere in fact that the imprint continually lives up to its very name in articulating ambiguous and “vertiginous” relations with a wide array of traditions which include, but are certainly not limited to, the Gothic, pulp fiction, and/or DC’s back catalogue.

This being said, I believe it makes sense to argue that Vertigo has developed a rewriting ethos which, since its early years, has taken many guises and shapes. Recent examples corroborating the idea that the imprint still plays with this trope of rewriting would include Brian Wood et al.’s revisiting of sagas in Northlanders or Ronald Wimberly’s Prince of Cats ( a “hip hop retelling” of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet that focuses on Tybalt). In short, while far from neglecting their influence, I’m trying to go beyond the celebrating of the early years and titles of the imprint. Rather, my aim is to look at the ways in which Vertigo developed a coherent while yet sometimes ambiguous editorial project over the years – a project that I believe cannot only be reduced to the eccentric character, edgy, and possibly drug-enhanced titles of the early 1990s.

LikeLike