1. Introduction

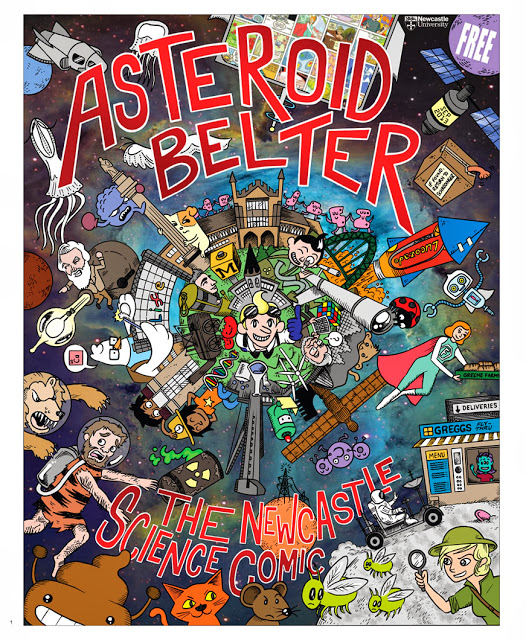

Asteroid Belter: The Newcastle Science Comic is a 44-page, newsprint, 10000 copy print run comic for the British Science Festival 2013 hosted by Newcastle University, England. It was produced as collaboration between a total of 76 artists, writers and scientists, led by our editorial team: Lydia Wysocki, Paul Thompson, Michael Thompson, Jack Fallows, Brittany Coxon and Michael Duckett. The comic sought to put university science research and concepts into the hands of children in a way that is meaningful, interesting, and inspiring to them. We did this by supporting scientists and comics creators to work together and increase each party’s understanding of the value of the other’s work. This article first outlines how we made Asteroid Belter, where we locate it in the wider field of comics, and then goes on to identify what we can and cannot show as evidence of its success.

2. What it is and how we made it

The foundations for Asteroid Belter were laid with the Paper Jam Comics Collective (PJCC), based in Newcastle upon Tyne. The PJCC formed as a social group for comics creators and fans in Newcastle to meet up and discuss comics and quickly became focused on creativity, both individually and as a group. There are many comparable comics groups across the UK (for example, the Manchester Comic Collective, the Bristol Comic Creators) and members soon began working together to create comics. The group has produced ten anthologies of varying degrees of professionalism on a range of themes, sold at events such as gallery launches, gigs and DIY markets.

Lydia Wysocki, a PJCC member and Newcastle University member of staff, was approached by the University’s Engagement team who were preparing to host the British Science Festival in 2013 (BSF13) to see if there would be any interest in working together to produce a comic as part of BSF13. The BSF, the British Science Association’s flagship event, is ‘one of Europe’s largest celebrations of science, engineering and technology’ (BSA 2014). The overall aim of the BSA is to advance the public understanding, accessibility and accountability of the sciences and engineering in the UK, with a broad view of which subjects are considered science. Whilst there are specific educational elements within the BSF, particularly its Young People’s Programme, it is not a direct extension of the National Curriculum in science and involves broad range of activities.

When Lydia brought the idea of a BSF13 comics project to PJCC it was met with enthusiasm. It was also clear that the structured nature of what would become Asteroid Belter in terms of project management, content, and presentation, meant this project was already different from PJCC’s participative nature. We decided to establish a special projects unit with invited members from PJCC. This meant we could work with Newcastle University to resource and deliver an ambitious anthology project, to establish a project management structure that would work for us, and to continue enjoying PJCC meetings.

Discussions with the Engagement team helped determine format and processes. Funding from Newcastle University’s Ignite small grants scheme was itself innovative as part of BSF13. As one of the first and largest projects funded in this way our project management was by necessity innovative, finding ways to work collaboratively and align this with NU’s reporting mechanisms. Choosing an anthology format meant we could include diverse styles (Smith, 2014) and content to increase the likelihood of readers engaging with at least some of the comic’s content as a pick ‘n’ mix approach. Establishing each page as a subproject maximised opportunities for many scientists and comics creators to have meaningful involvement in and ownership of the project. Staggered start dates for 8-week subprojects with editorial checkpoints mitigated risk around adherence to brief and deadlines. This structure helped us plan the time and skill commitment of Asteroid Belter and identify appropriate rates of pay against industry standards and Newcastle University’s pay scale. Sharing test printings with the Engagement team, and through them the Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Executive Board, demonstrated our progress and aligned Asteroid Belter with Newcastle University structures. Our experience of comics projects helped us find suitable printers and work with them to quote for test and final printing costs.

We broke the initial tasks of beginning the comic into the following steps:

– Approach comics creators to see if they would be interested in taking part in the comic – this involves sending some individual invitations, and an open call promoted online and at Thought Bubble 2012.

– Discuss the project with scientists at a Newcastle based SUPER MASH UP event, where we gave a brief overview of how we saw the project working and gave an introduction to comics to those unfamiliar with the medium; we followed up by email and phone with contributors unable to take part in the SUPER MASH UP in person.

– Ask all scientists and comics creators (whether artists, writers, or sole creators) to fill in the same expression of interest form to give us an overview of their work and any initial ideas they might have.

– Match comics creators with scientists as page teams, and assign each team a page editor to establish communication between scientists and comics creators. This was done in editorial “stables”, with each page editor having an overview of 5 or 6 pages.

As a pilot project we worked with three comics creators to produce a three-page activity pack to be distributed to Newcastle University’s partner schools in preparation for BSF13. The school activity pack was worthwhile in its own right, as a set of worksheets exploring the difference between science fact and science fiction, and as a pilot phase for our processes and outputs. Feedback from schools helped adjust guidelines for artists/writers. This feedback continued in reviewing draft artwork and test printings among editors and with one editor’s class of 8 year olds. The school activity pack was also important to the participative elements of Asteroid Belter: the third worksheet was a comics creation challenge, the prize for which was publication in our comic. We also held an open call for online submissions to be shared through our blog, to invite contributions from creators unable to take part in the printed comic. On our launch day we took over Newcastle City Library with structured comics workshops and drop-in activities for children and families, and ran pre-launch comics making activities at BBC The One Show’s summer festival in Gateshead. This participative focus was important to us. We agree with Green (2013) and Williams (2013) that both reading and creating comics matters, particularly for students’ understanding of medical issues: Green’s point about students becoming ‘more careful observers’ (Green 2013, p. 474) and Williams’ discussion of the accessibility of comics as medical narrative (Williams 2013, p. 27) are particularly relevant here. We extend this to our broader scientific as well as medical content, and beyond students and health professionals to the wider public.

It is worth noting that whilst some scientists involved in the project had used comics in their work before, often as a tool of public engagement, the majority had not had this experience. Some comics creators had worked on commissioned educational projects before, but again this was a minority. In neither case did we specify that contributors had to have worked on comparable projects before, and our contributors included undergraduate and postgraduate student scientists and artists/writers. EPIC THEMES in AWESOME WAYS was our terminology for mixing huge themes in science research (including explosions, time and travel, and hidden messages) with comics structures and tropes (including biographies, stories, and diagrams). This helped researchers connect with comics creators who otherwise had little shared professional language (Mercer 2000), to generate, maintain, and channel awesome levels of enthusiasm.

From the start of this science comics project we were clear that the science and the comics were of equal value. We are aware of other projects using comics (for example Magreet de Heer’s Science: a Discovery in Comics, and Leeds University’s Dreams of a Low Carbon Future), as a format to communicate science. Asteroid Belter is fundamentally different because we wanted to see what happens when comics and science collide: neither the comics nor the science element is in service to the other. Treating each page as a sub-project maximised the opportunities for many contributors to have meaningful involvement in and ownership of the anthology. Scientists were involved throughout the project first as sources of inspiration and information, and on an ongoing basis as consultants for the accuracy of each comic. This also gave comics creators scope to explore a manageable piece of science research rather than attempting to fit their contribution into a longer narrative. Within each scientist/comics creator team it was the comics creator who led the creative process with the editor keeping this on track with the larger aims of the anthology: this required trust from all members of the project team. This structure was our way of ensuring a final comic that was a comic, not an illustration of research findings or a colourful textbook (figure 1).

Figure 1 Ian Mayor and Will Campbell, extract from ‘Time Travel is Awesome’ in Asteroid Belter: The Newcastle Science Comic. Newcastle: 2013.

The page editor role was an interesting one. We remain aware of key issues in the comics field, particularly around diversity in our choice of contributors and the content and characters they produced (Havstad 2014). Specific issues we discussed in editorial meetings included gender, race, age, dis/ability, and professional experience in publishing comics. We did not set quotas for who should participate or what they should create, other than specifying which scientific research each page would cover. We do not claim Asteroid Belter as a flawless example applying this in practice, but are proud of the comic we created and confident that we did our best to understand and act on issues within this project.

3. Our evidence that Asteroid Belter worked

Asteroid Belter is a project firmly rooted in comics practice. We are mindful of relevant research and theory from comics scholarship (as cited in our list of references), and also from our backgrounds in librarianship and education. Whilst aware of comics projects set up as research projects with clear ontological frameworks and research questions, we cannot overstate that we chose a well-informed focus on practice. This limits what evidence we can present of Asteroid Belter’s success. We did not set out to test a hypothesis. Comics scholarship includes many calls for increased evidence, particularly statistical evidence, of the extent to which comics work in education (for example, Caldwell 2012). Tempting as it is to look back and construct an argument for what we could have proven, we will instead present the evidence that emerged from our project and highlight what this does and does not reveal.

It is also worth noting that much of the ‘comics in education’ debates and literature focus on formal education systems, as schools. Moeller (2011) is a particularly strong advocate for the inclusion of graphic novels into the school curriculum. Spiegel and colleagues’ (2013) focus on engaging teenagers with science emphasises a need to ‘engage all teenagers, even those with low science identity’ (Spiegel et al. 2013, p. 2309), but their study focusses on students enrolled in ninth and tenth grade biology classes. We respect the work of these examples but note that they are all bounded by the structures and limitations of formal education systems. This is not to belittle the effort involved in including comics in formal education systems: Laycock’s (2013) discussion of how librarians and teachers have needed to be ‘opportunistic and largely self-driven in their acquisition of knowledge and skills regarding graphic novels’ highlights this. The School Library Journal has a dedicated graphic novel section that supports this professional community, particularly through the work of Brigid Alverson.

Asteroid Belter’s position as part of BSF13, not within a school system, meant we went outside the existing UK school system. We also considered what might be possible beyond existing school structures, informed by more radical educational thinkers (Neill 1970; Vygotsky 1978). This is ideologically interesting but, at a more practical level (and resisting a diversion into discussion of schools and other forms of education), makes evaluation of Asteroid Belter tricky. It was not possible to track which individuals read our comic and as we will show, difficulties in identifying the demographics of our readers make us unwilling to use an artificial matrix to select a sample group. This section first considers what evidence we gathered as evidence of participation, public engagement, and readership, then presents considerations relevant to what readers and other key individuals took from the project.

A. Evidence of participation in creating the comic

We received 112 expressions of interest in participating in creating the comic and were able to invite 74 people to take part in creating the comic, all of whom are credited in in print and online. We were easily able to find replacements for the two comics creators who withdrew from the project because of other commitments; no scientists dropped out of the project. As this was our first large-scale edited anthology project, and without access to data on comparable anthology projects’ participation rates, we do not know how these numbers compare to the field. We were pleased to receive interest from more than enough people to create a substantial anthology. It is worth noting that our call for contributors was open to all, regardless of whether we knew them prior to this project or whether they had previously undertaken comics work that was educational, based on science, or published (we were later asked by our funders to prioritise contributors from the North East of England). Receiving expressions of interest from people we did not know is evidence that word spread about our project.

The fact that we delivered a collaboratively-produced comic is evidence that our project succeeded, and this is further supported by positive comments we received from contributors about their involvement in the process of creating Asteroid Belter, for example:

It is a really fantastic project, and really well managed too! [We] are proud to be a part of it, and I hope it continues to be a feature of the BSF for years to come!

and comments from scientists who had not previously been involved in making comics, for example:

I think it’s fantastic and had to struggle hard to stop reading it this morning, so I could do some work.

Academic staff involvement in public engagement projects is typically part of a diverse and full workload, so our evidence of success is the fact that the project delivered a completed comic and that this was received well by participants

B. Evidence of public engagement

The overall evaluation report of BSF13 covered all aspects of the Festival and included interviews with adults whose children took part in our Asteroid Belter launch day events. The report’s overall findings were positive, for example that 94% of visitors [respondents] indicated that they thought the quality of the content of their event was ‘Excellent’ or ‘Good’. [587 individuals (25% of total visitors to ticketed events) who submitted a completed questionnaire; number of total unique visitors was in the region of 19000]. We are cautious in how far we can apply these headline findings to our comic. The fact that Asteroid Belter was mentioned without prompting evaluation interviewees and is noted in this overall evaluation is positive news, particularly as this was the first time a comic was created as part of the BSF. The BSF13 evaluation’s necessarily high-level focus on footfall and satisfaction means we now turn to other indicators for a closer look at who read Asteroid Belter and what they said about it.

C. Evidence of readership

Six months after our September 2013 launch, approximately 9850 of the 10000 printed copies of Asteroid Belter have been distributed. Some two thirds of these were given to participants in the Young People’s Programme of the BSF13. A further 1250 copies were picked up from distribution stands at Newcastle City Library, 600 copies distributed at Thought Bubble and Comics Forum Conference 2013, over 250 copies at Travelling Man Newcastle (and more through other comics retailers in the UK), and others in response to requests from local schools and youth organisations for additional copies. Asteroid Belter is free to read online and has been accessed 2,487 times since its launch. We recognise that giving away a free comic means we are not able to compare this to sales figures of other titles. We also note that we did not struggle to distribute these copies, and in many cases were asked for additional copies.

Having shown that Asteroid Belter found readers, the demographics of this readership are difficult to identify. Demographic data in the BSF13 evaluation report includes a note that approximately half of respondents had a professional reason for attending BSF13 (as students, teachers, or science sector professionals), with the other half of respondents identified as individuals with a general interest in science. Whilst this points towards a self-selecting audience group of people interested in science or otherwise connected with education or NU, this is not to detract from the response from our readers which was overwhelmingly positive.

These attendees are not representative of the general public, but nor are they a full picture of our readers. Getting university researchers to connect with 8-13 year old children as a valid and viable audience for their research was important as this age group is key to, yet often overlooked by, student recruitment and Widening Participation agendas. Though primarily a public engagement project this link with Widening Participation matters. Of the local primary and secondary schools who were given copies of Asteroid Belter at BSF13 and/or whose teachers contacted us for additional copies, some were in postcodes in the lowest quintile of participation in HE (POLAR, 2012). Before getting carried away praising Asteroid Belter’s success in engaging young people from low participation neighbourhoods with university-level science research (Newcastle University is recognised nationally for its work on widening participation in HE) we must note that other schools were in postcodes in the highest quintile of participation in HE. This is a complex picture.

4. Why this matters

We have established that Asteroid Belter engaged scientists and comics creators in the creation of a science comic, with both science and comics equally valued, and that the successful delivery of this project engaged members of the public in science and comics. We now turn to consider what readers took from the comic.

The communication of scientific concepts and research to readers is central to Asteroid Belter. That said, we were clear that Asteroid Belter should not be an educational textbook disguised as a comic. We made a conscious decision not to identify specific learning outcomes either for the anthology as a whole or for each individual comic, instead focussing on exploring what would happen when science and comics, as one of our editors put it, ‘collided’. This suggests two possibilities: a focus on learning outcomes and a focus on satisfaction.

Work by Ching and Fook (2013), Spiegel (2013), and others, has evaluated the effectiveness of comics they commissioned to communicate specific learning outcomes. This focus on comics as a method of communication suited their purposes but would not be directly transferable to our practice-based project. Asteroid Belter’s broad target age range, diverse science content, and deliberate lack of alignment with the National Curriculum priorities meant we could at best have tested whether a sample of our readers said that they had learned ‘some stuff’. This would be far from satisfying. Developing and validating effective research instruments to address this more systematically was beyond the scope of this practice-based project and, for us, could well have detracted from the fun of making and reading the comic. Quantifying the amount of enthusiasm conveyed by the comic would point towards a focus on readers’ professed satisfaction with the comic, which in turn raises questions around the validity of how to ask young readers “do you like this free comic we made for you?” With the appropriate rigour this could however be a fascinating area for further research, whether academic or market research, but was not the focus of our project.

A perennial issue in education research is that of whose opinions are valued. Is it children, parents, educators, or others who are best placed to decide whether a (young) person is learning? Educational experiments with child-led schools (Neill, 1970) and self-organised learning (Mitra and Rana, 2001) are interesting counterpoints to curricula prescribed by experts and governments. For brevity, we summarise our view on these educational debates as follows: young people’s views on their learning are valid, and the role of more experienced others (Vygotsky 1978) in guiding their learning is important. In this context we note that we received unsolicited positive comments from the Service Manager (Children and Young People) of Newcastle Libraries, the Education Director of the British Science Association, and the Head of Quality in Learning and Teaching at Newcastle University. These are all individuals whose roles are relevant to our project: their opinions are encouraging and we are grateful for their support, and if we had been conducting a research project we would have probed their opinions further. We are particularly happy about having seen children reading Asteroid Belter and drawing their own comics (figure 2) – and frustrated that, having spotted children doing this, the official photographer had to interrupt them to ask their parents to sign photo release forms, then ask children to pose exactly as they had been. This email from the parent of our first reader is something we are particularly proud of, so is something we share here both to show off and to indicate the richness of data that might be available for others to investigate:

Just a note to tell you how much [my daughter] absolutely LOVED the comic. Seriously loved it! She’s just gone five and I wondered if the content might lose her a bit but I was wrong! We read it from cover to cover on the metro coming home and she had lots of questions about tricky things like cancer cells but at the end she exclaimed ‘mammy that was fascinating!’ Now that’s endorsement! She wriggled through Disney’s Monsters University earlier in the day but was glued to your comic. A scientist in the making I hope!

Figure 2 photo of children drawing at our launch day events at Newcastle City Library (photo courtesy of Newcastle University).

We earlier noted questions around the validity of asking children whether they liked our comic. Future research to investigate whether our readers went on to study and work in science and science communication could be illuminating, particularly if we were able to compare this to regional and national data on work and study. All this however assumes academic progress as an indicator of engagement with science: the BSF13 evaluation report’s category of ‘individuals with a general interest in science’ notes that engagement with science can be distinct from work or study in the field. There are further questions of the extent to which we could attribute any findings to Asteroid Belter. We also note that aspects of the BSA, City Library, and Newcastle University’s work necessitate a focus on marketing and footfall. Similarly, whilst we appreciate our positive reviews from the comics press (we were interviewed by Graphixia and Comics Beat, and reviewed by Forbidden Planet and Starburst Magazine), we cannot equate these to research evaluation of our project. Whilst pursuing this as research could be fascinating, our approach is to be aware of these larger issues as we focus on the practice of making comics.

5. Conclusion

The Asteroid Belter project has been an enjoyable one, and has raised questions and opportunities for further research. Planning and editing the comic was approached in a thorough fashion, and resulted in a finished product produced to professional standards and contributors who were paid accordingly for their work. As our project was focussed on comics practice it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about its educational value. There are encouraging signs that Asteroid Belter was received positively by its intended audience of 8-13 year olds, their families and teachers, and also by comics readers and creators, and colleagues in key educational roles. We have demonstrated that there is an audience for science comics in which both science research and comics are equally valued, rather than more prevalent models in which comics are a vehicle for the delivery of science. Our future projects will take into account the issues included in this article, and we invite others to make use of our experience.

References

BSA: British Science Association [website], ‘About the British Science Festival.’ http://www.britishscienceassociation.org/british-science-festival/about-festival

Caldwell, J. (2012). ‘Information comics: An overview.’ Professional Communication Conference paper, Orlando, FL. Available online: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/login.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6408645&url=http%3A%2%2Fieeexplore.ieee.org%2Fiel5%2F6391318%2F6408590%2F06408645.pdf%3Farnumber%3D6408645

Ching, H.S., and Fook, F.S. (2013). ‘Effects of multimedia-based graphic novel presentation on critical thinking among students of different learning approaches.’ Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technologies, 12 (4), pp. 56-66.

Flo-culture (2014). British Science Festival Newcastle 2013: Evaluation report. Newcastle University and the British Science Association. Available online: http://www.britishscienceassociation.org/british-science-festival/evaluations-previous-festivals

Green, M.J. (2013). ‘Teaching with comics: A course for fourth-year medical students’ Journal of Medical Humanities, 34, pp. 471-476.

Havstad, J. (2014). ‘Using comics to teach Philosophy, inclusively.’ Comics Forum, available online: https://comicsforum.org/2014/01/17/using-comics-to-teach-philosophy-inclusively-by-joyce-c-havstad/

Laycock, D. (2013). ‘Keep watering the rocks.’ Comics Forum, available online: https://comicsforum.org/2013/09/20/keep-watering-the-rocks-by-di-laycock/

Mercer, N. (2000). Words and minds: how we use language to think together. London: Routledge.

Mitra, S., and Rana, V. (2001). ‘Children and the internet: experiments with minimally invasive education in India’. British Journal of Educational Technology, 32 (2), pp. 221-232.

Moeller, R.A. (2011) ‘“Aren’t these boy books?”: High school students’ readings of gender in graphic novels.’, Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 54 (7) pp. 476-484.

Neill, A.S. (1970). Summerhill: A radical approach to education [New Impression edition]. London: Penguin.

Participation of Local Areas [POLAR], (2012). Map of young participation areas [online map]. Available online: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/whatwedo/wp/ourresearch/polar/mapofyoungparticipationareas/

Smith, P. (2014). ‘Maus in the Indonesian classroom’. Comics Forum, available online: https://comicsforum.org/2014/02/18/maus-in-the-indonesian-classroom-by-philip-smith/

Spiegel, A.N., McQuillan, J., Halpin, P., Matuk, C., and Diamond, J. (2013). ‘Engaging teenagers with science through comics.’ Research in Science Education, 43, pp. 2309-2326.

Ujiie, J & Krashen, S. (1996) Comic book reading, reading enjoyment and pleasure reading among middle class and chapter 1 middle school students. Available at: http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/articles/comicbook.pdf

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. [eds. M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S Scribner, E. Souberman]. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press.

Williams, I.C.M. (2012). ‘Graphic medicine: comics as medical narrative.’ Medical Humanities, 38, pp. 21-27.

3 responses to “EPIC THEMES IN AWESOME WAYS: How we made Asteroid Belter: The Newcastle Science Comic, and why it matters by Lydia Wysocki and Michael Thompson”