Background

Denmark and Greenland have, for a long time, been historically connected; in 1721 the Danish/Norwegian priest and missionary Hans Egede travelled to Greenland in search of the Norse. He didn’t find them, as the Norse had disappeared at the start of the 15th century. He did however find the Inuit, and he focused his missionary activities on them instead. In 1728, Egede founded the colony Godthaab (which is now known as Nuuk, the capital of Greenland today), and until 1953 Greenland was considered a Danish colony. In 1953, Greenland became a part of the Danish realm under the constitution of Denmark. Greenland received Home Rule Government in 1979, and in 2009 this Home Rule Government was extended to Self Government – although the Danish monarch is still the head of state in Greenland. Since the 19th century, Danish (and later also Greenlandic) scientists have been working in Greenland, documenting everything from archaeology, anthropology and language, to geology, biology and glaciology.

Introduction to the graphic novels

In 2006 the SILA – the Arctic Centre at the Ethnographic Collections in the National Museum of Denmark – won a prize for the most dynamic research community. The archaeologists and historians at the department discussed how to use this money, and they came up with the idea of asking the artist Nuka K. Godtfredsen whether he was interested in making four test pages – each page representing one of the migration periods in the prehistory of Greenland. Nuka accepted, and these four pages led to the idea of making four graphic novels, in a cooperation between Nuka, the National Museum of Denmark, the schoolbook publisher Ilinniusiorfik in Greenland, and the Greenlandic newspaper Sermitsiaq.

In 2009 the first book, The First Steps, was published. The First Steps is about the first migration from Canada to Greenland 4500 years ago by a group of people named “the Independence people”. The comic book was made in a cooperation between Nuka and the researchers Dr. Bjarne Gronnow and Mikkel Sorensen. The Independence people lived approximately around 2200 BC, and they travelled from Northeast Siberia, through Alaska and Canada, to the Northeast coast of Greenland. The Independence people did not use kayaks or dog sleds like the Inuit. Instead, they were hunters living off musk ox, seals and fish.

In The First Steps Nuka used the archaeological findings as a starting point, making up his own story about the boy Nanu (a name that means “polar bear”). After a vengeful attack on his group, Nanu and his family travel east to the unknown land (Greenland). However, the lack of food and bad ice conditions cause most of the family members to die. Later on in the book, Nanu – who is now a grown up man – successfully travels to Greenland, where he settles and meets one of the other migrant groups, the Saqqaq people.

The book received great reviews, and because of this positive response the publisher and the researchers agreed to create one more book. Three years later, in 2012, the second book, The Ermine, was published. This book is about the pre-Inuit “Dorset-people” – named after the findings at Cape Dorset, Baffin Island – and it is set in the 12th century. In Greenland there are three different migrations of the Dorset, which took place between 800 AD – 1300 AD. The book The Ermine is about the last of these Dorset-migrations and it is set in the North of Greenland. The story, which was written by Nuka and the archaeologist Martin Appelt, mainly focuses on shamanism. In the story the reader follows a Dorset woman that travels from Canada to Greenland while, at the same time, the book shows her transformation from being a depressive and strange woman to becoming a shaman.

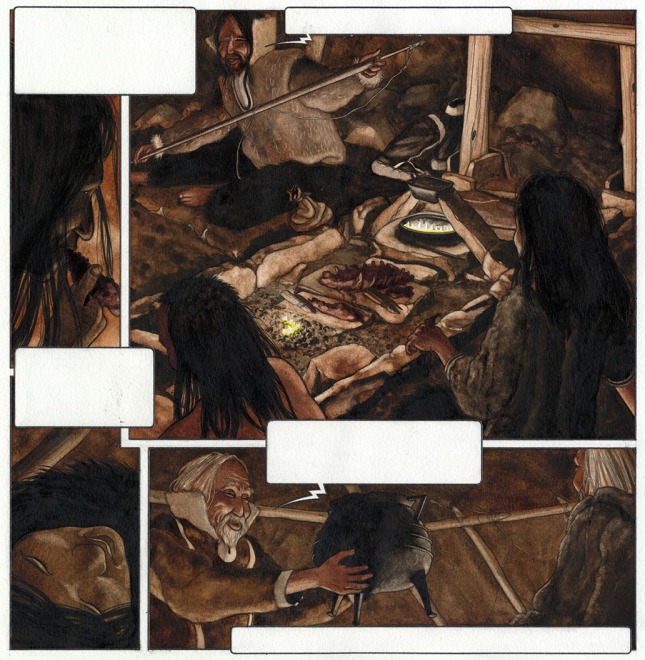

As with the first book, the story was based on archaeological finds and theories. For instance, archaeological discoveries have shown that the Dorset people had a certain way of placing the stones in the middle of the tent. They also had some form of trading with the Norse, as certain elements from Norse culture – like pots – were found in the Dorset settlements in the north of Greenland. Both of these examples, the placement of stones and the trade relations with the Norse, are shown in figure 1a (sketch) and 1b (p. 10 in the book). Other archaeological findings are from the Dorset culture. The archaeologists have found a lot of figures cut out from bone, which seem to represent the Dorset themselves. A figure like this is shown in the drawing in figure 2 (p. 51 in the book).

Figure 1b: These drawings show the trade between the Dorset people and the Norse. The pot shown is based on archaeological finds from Avanersuaq (North Greenland).

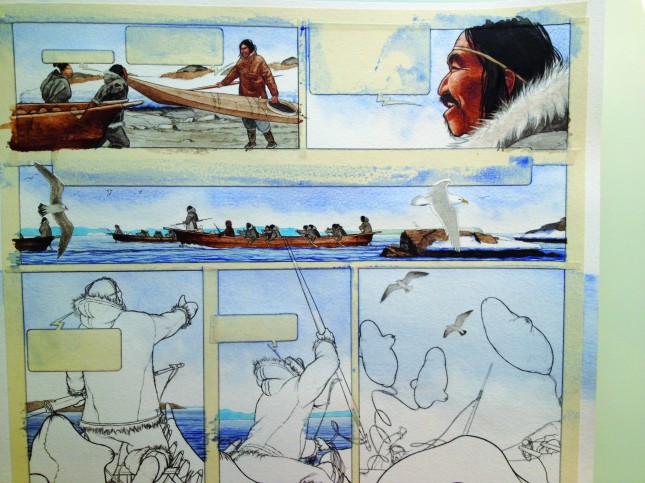

At the moment, Nuka is working on finishing the last pages of the third book, The Gift, which will be published in 2015 (see figure 3). This third book is set in the 18th century and it tells the story of European and Inuit whale hunting in Greenland, their trade, and the European mission. The story is based on the family saga of “Qajuuttaq”, which is told from generation to generation in Greenland. The main character, the Inuk (singular of Inuit) Qajuuttaq, grows up in the area around the colony Godthaab. He lives with his family, and now and then they visit the colony and Hans Egede. Hans Egedes’ son Niels tells Qajuuttaq about the different European traders and whale hunting ships. When Qajuuttaqs’ parents die of the smallpox, Qajuuttaq cuts out a tiny kayak as a gift to put on top of their grave. When he goes whale hunting and trading with other Inuit, Qajuuttaq trades with another Inuit man, named Asaleq. Asaleq gives him the tiny kayak that Qajuuttaq made for his parents’ grave and it becomes clear that Asaleq has stolen the gift. An angry Qajuuttaq kills Asaleq and flees down South. When, during one of the winters, a Dutch whale hunting ships sinks, Qajuuttaq saves the sailors by allowing them to stay in his small settlement. Among the sailors are the captain and his son, Emiel. Emiel and Qajuuttaq strike up a friendship and the Inuk teaches the boy some Greenlandic, as well as how to sail the kayak. In the spring, the Dutch sailors get the chance to go back to Europe, and Qajuuttaq gives the tiny wooden kayak to Emiel. Qajuuttaq is still followed by the sons of the killed Asaleq, and he therefore continues down the coast to the South of Greenland. At the end of the story, Qajuuttaq dies an old man. Shortly after his death, Emiel returns to Greenland, trying to find Qajuuttaq in order to give back the tiny kayak. He finds his grave and puts the kayak on top of it. The gift thus returns to its maker.

All three books are published in Greenlandic, Danish and English (The Gift will be published in all three languages around summer 2015), and in the spring of 2015 the first book, The First Steps, will be published in Japan.

Figure 3: An example from The Gift. Nuka holds up a photograph taken in the Nuuk Fjord. As you can see, Nuka has redrawn the landscape, adding an umiaq (the boat in which women and children travelled) and kayaks (with the men) around it.

The process

The first two books, The First Steps and The Ermine, were based primarily on limited archaeological findings and research, so that Nuka had the possibility of using his own fantasy for substantial parts of these two stories. Because of the “holes in the knowledge” about these ancient peoples, the researchers do not know the exact details about everyday life, such as their clothing and daily activities. These gaps in knowledge also influenced the cooperation with the researchers, because when Nuka asked questions about the daily lives of these ancient people, the researchers had to take another look at their theories and discuss the details again. For instance, Nuka used his own fantasy for the drawings of the clothes and tents of the Independence people. Scientists haven´t found any remains of their clothes, nor do they know much about the exact design of the tents. However, they do know which animals were hunted and they have found some remains of the tents. In The First Steps, p. 22 (figure 4), the drawings show a combination of exact archaeological knowledge and fantasy. On the one hand, the clothes are “made up” by looking at the types of fur available at the time (combined with the hunting weapons), and by tracing how more recent inhabitants of the Arctic make their clothing. On the other hand, the drawings of the lashing of the bows are based on exact knowledge about these weapons. Another example is the way in which the scenes of shamanism are shown in The Ermine p. 28-29 (figure 5a & b): Here you see Nuka’s interpretation of the angakkoq (the shaman) receiving a new “helping spirit”. The pages preceding this scene show the killing of a grizzly bear. Because of the very close relationship between the ancient peoples of the Arctic and nature, the shaman asks the dead grizzly bear if it can forgive him for killing it. In the evening the shaman travels with his spirit, meeting and then becoming the grizzly bear, after which he returns to his own body. Of course it is not possible to find archaeological evidence for this kind of spiritual travelling, but the archaeologists have found a lot of figures showing this type of religion.

Because the third book, The Gift, takes place in the 18th century, the researchers know a lot about the details of the different events that took place. They have texts and findings that give a lot of information about clothing, ships, houses and the mission, as well as the techniques of whale hunting used by the Europeans and the Inuit. With this huge knowledge as starting point the process has been much stricter than that of the first two albums.

Figure 4: This hunting scene shows a mix of archaeological finds (the bow and arrow), and Nuka’s imagination (the clothing).

Figure 5b: These drawings show two pages from The Ermine, demonstrating that the Dorset people believed in shamanism.

How the third book is made

It is a long and demanding process to make this kind of graphic novel. In the summer of 2012, Nuka began researching this particular period in Greenland. Dr. H.C. Gullov from the National Museum of Denmark created a list of the most important historical sources, archaeological findings, and events from the 18th century in Greenland. This became a long list of things that Nuka could choose from during the creation of his story. However, the list of resources, specific years and historical figures was so complex, that Nuka and I decided to create the story together. Since 2004, Nuka and I have been working together, creating different kinds of children’s books, comic books and articles that, directly and indirectly, tell about Greenlandic culture and nature – as well as dealing with basic life as a human. These human themes also form an important part of our children’s books. Even though there are obvious differences between children in terms of their culture, language and climate, we explore basic necessities; all children need their parents and a safe environment, and children use their imagination to play, learn, and fantasise. So, as partners in private and as colleagues in these creative projects, I (having a master’s in Arctic Studies and being a writer) tried to help Nuka to understand the academic way of working and talking. The next step was to transform the academic knowledge into drawings and text bubbles.

In the third book we tried to combine the many sources with the findings, making a coherent story by filling the gaps in knowledge with imaginary people and events. We needed to make an imaginative story based on facts and put into a frame of disseminating archaeological and historical knowledge. The archaeologists and historians know a lot of details from the diaries of the Egede-family, the remains from the houses (both the Danes and the Inuit) and elements from daily life, like clothing and trading goods. What we didn’t know about in detail was the Inuit way of thinking. All the written materials are from European missionaries, traders and whale hunters. And on top of this, it was forbidden to trade with the Inuit. Archaeologists have found remains of, and documentation on European trading goods among the Inuit, like the beads known from the modern traditional national clothing in Greenland. But as this barter was illegal, no one has written about it in the official logbooks (see figure 6a & b).

Figure 6b: Two drawings from the third book, The Gift. One of the aims of this book is to show meetings between different cultures. These drawings show an encounter between the Inuit and the Dutch whale hunters.

Professor Pauline Knudsen from the National Museum of Greenland gave us the idea of using one of the many oral stories about the family saga of “Qajuuttaq”. With this story and its main character as starting point we slightly changed the historical period in which it is set, while adding some well-known historical figures and strictly following the historical facts of the specific years, places and finds. This storyline went back and forward between us and Dr. Gullov, until the text was ready. In the summer of 2013, Nuka and I visited Greenland for three weeks travelling around in the areas where the story takes place, so that we could take pictures and visit the places where the protagonist of the story “lived”. During this journey we used the opportunity to offer free workshops for children and to give lectures about the project in the local communities.

Since then Nuka has been working on sketches with pencil, colouring the drawings with watercolour painting and writing texts in the bubbles (figure 7). Everything is made by hand, except for the texts, which are made in the computer in order to change the languages. This handmade quality means that it takes about one month to make two pages. Nuka and I have made a short video showing how he works on the creation of one page.

Figure 7: An example of the drawing process. Nuka has drawn the sketch on watercolour paper, after which he covers certain areas with tape and colours in the rest.

Now, the third book is almost finished, and because of the success of the first two books, the Greenlandic publisher and the National Museum of Denmark have already agreed to make the final, fourth book. This last book will be about the Norse settlements in Greenland (people coming from Iceland) at the end of the 14th century. As in the third book, the researchers know a lot about these people and their way of living, and because of this high level of knowledge, Dr. Jette Arneborg (researcher at the National Museum) and I have already begun writing the storyline. In order to show some of the newest results of the archaeology and climate research, the story of the Norse takes place at the end of their time in Greenland. For many years it has been discussed how and why the Norse disappeared from Greenland, and because the scientists now have quite a good idea about the combination of different reasons why they disappeared, this will be the main focus of the story.

The archaeologists have a lot of findings from the Norse. Taking these findings as a starting point, I have written a story about a Norse woman, Bjork, and her family. Her husband, Bjarne, travels with a group of men to the North of Greenland to trade with the Inuit coming in from the Northwest (Canada). Bjarne violates some of the most important religious rules, which negatively influences his relationship to Bjork. She starts to doubt her marriage to Bjarne and travels to Norway on a pilgrimage. As Catholics in the Middle Ages the Norse lived in a very strict and religious society, and in the story it has been my aim to show two sides of this fact. It shows how difficult it must have been to live by strict Catholic rules in a country far away from everything that is familiar and in a climate getting colder and colder, and it shows what it is like to meet people from a completely different culture (the Inuit). The story will be about survival in the Arctic, meetings of cultures, religion, and the doubt about one’s own actions and choices; all of this put into the frame of the archaeological findings from the Norse.

The book is to be published in a couple of years.

Nuka K. Godtfredsen was born in Narsaq, Greenland, 1970. He is an autodidact artist now living in Copenhagen. He has made a lot of illustrations for books and stamps, and his work has been shown at different exhibitions in e.g. Alaska, Iceland, The Faroe Islands, Sweden and Denmark.

Lisbeth Valgreen was born in Copenhagen, has a master in Arctic Studies from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark and Nuuk, Greenland. She has written several children’s books and articles.

Fig. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8: © Nuka K. Godtfredsen & National Museum of Denmark

Fig. 3 & 9 Photo: © Nuka K. Godtfredsen