The Superman “shield” most familiar to contemporary readers is a pentagon. Emblazoned on his chest, it is a recognizable symbol of the “first superhero” whose emergence in Action Comics in 1938 gave birth to the genre most associated with the history of American comics. Interestingly, however, the symbol has little resemblance to that which first appeared on Superman’s chest in his debut. In those early days, Superman, created, by Jerry Siegel (writer) and Joe Shuster (artist), had a simple triangle on his chest, with a sinuous “S” in its center. The shift in insignia is largely insignificant, but the original shape is reflective of the ways in which those early stories revolve around a “love triangle” that is both familiar and unconventional. [1]

In those stories, Superman is not the stoic, conservative, and nearly omnipotent being he became over the course of subsequent decades. Instead, he is a daring, carefree, wisecracking daredevil who is something of a New Deal semi-Socialist, fighting big business and corrupt capitalism in his role as “champion of the oppressed.” In this, Superman supposedly evens the scales, by becoming the symbolic “power of the people.” Opposing himself to unfair power, however, he also ironically becomes that which he opposes. More than balancing the scales, he becomes irresistible, forcing others to accede to his will, even as he represents the powerless whose will is subjugated.

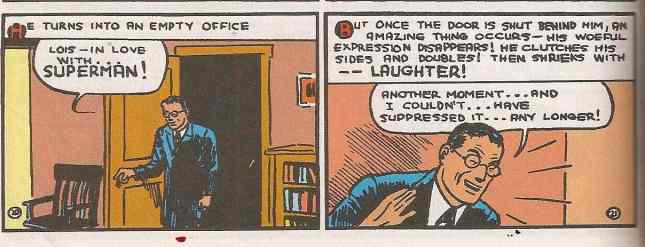

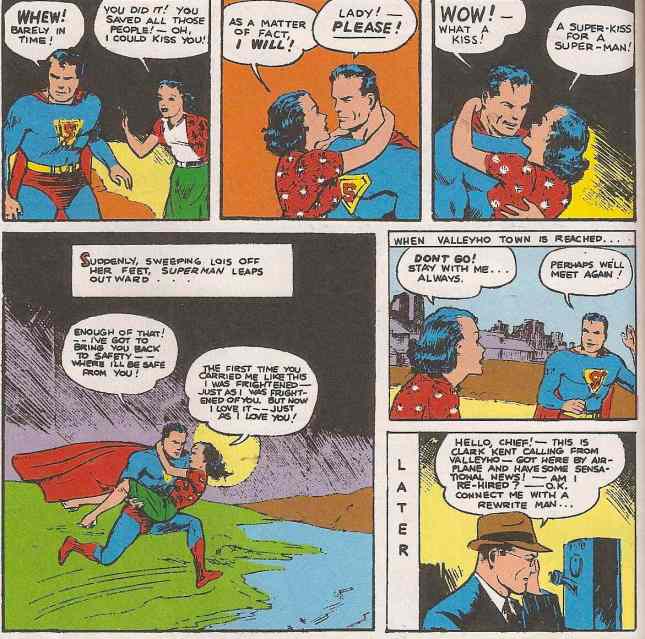

Something of the same dynamic appears in Superman’s “private,” or romantic, dealings with Lois Lane. There, reflecting his insignia, Superman is involved in a “love triangle.” At two vertices of this triangle are the two identities of Superman, the superhero himself and his timid/weakling alter ego, Clark Kent. The third is occupied by Lois, the intrepid reporter for the newspaper at which Kent also works. Kent is in love with Lois (or claims to be) and perpetually wishes, at the very least, to take her on a date, while Lois, of course, falls for Superman, the ‘he-man’ that appears to be everything Clark is not. Just as Lois rebuffs all of Clark’s advances, however, Superman rejects hers, taking a kind of perverse pleasure in revenge for her mistreatment of his “other self” and laughing at her behind her back.

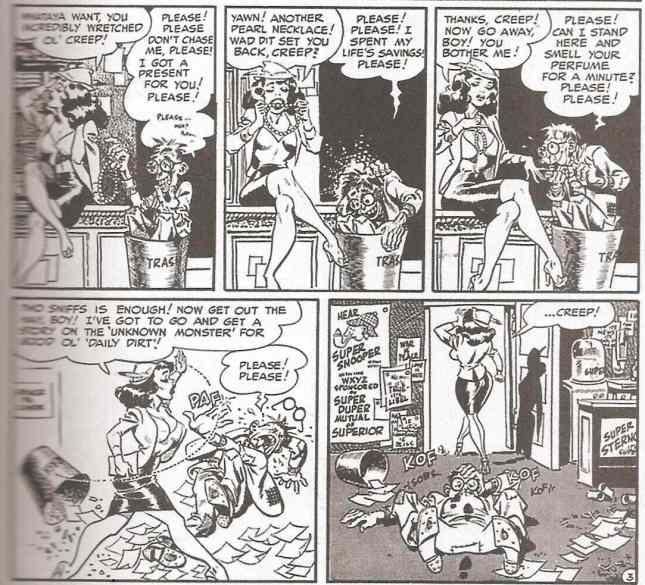

The early Superman’s private life is then built on an unrelieved sexual tension, with Superman preferring to punish Lois rather than bed her and/or wed her. In this, the “Man of Steel” is able to retain his phallic hardness indefinitely, a model of potency that can never be deflated even temporarily, as it might be through its satisfaction. At the same time, while conventional sexual pleasure is never part of these stories, there is a kind of “perverse” pleasure achieved through Superman’s perpetual scorning of Lois (and Lois’ of Clark). Sexuality is here a kind of sadomasochistic game of teasing and scorn, the elements of which were keenly satirized by Harvey Kurtzman’s ‘Superduperman’ in MAD in 1953, some 15 years after Siegel and Shuster’s initial stories.

In Les Daniels’ history of the Golden-Age Superman, he notes that ‘from today’s perspective, it’s easy to denounce Lois as the misogynist fantasy of a disappointed male’ (20), an idea he introduces only briefly in order to skim over its ramifications and proceed on to other things. While it is not my purpose here to critique Superman’s creators for misogyny, I would like to look at Daniels’ brief comment a bit more closely. To do so, it is worth revisiting Siegel’s account of the origins of the Superman/Clark/Lois triangle.

…As a high school student, I thought that some day I might become a

reporter, and I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn’t know I existed or didn’t care I existed…It occurred to me: What if I was real terrific? What if I had something special going for me like jumping over buildings or throwing cars around or something like that? Then maybe they would notice me. That night when all the thoughts were coming to me, the concept came to me that Superman could have a dual identity, and that in one of his identities he could be meek and mild, as I was, and wear glasses, the way I do. The heroine, …a girl reporter, would think he was some sort of a worm, yet she would be crazy about the Superman character…and a big inside joke was that the fellow she was crazy about was also the fellow whom she loathed…

It is one of the most clichéd and most reiterated claims about superheroes that they are simply a fulfillment of “power fantasies,” allowing adolescent readers to live out their previously frustrated desires, especially of being attractive, powerful, and popular. In the same interview, Siegel says as much, calling Superman a version of ‘wish-fulfillment,’ not only for himself, but for those readers who were ‘similarly frustrated.’

This is, perhaps, where charges of misogyny could be leveled, since one would think that the “natural” wish that the scorned, ignored, or rejected straight male would want fulfilled would be the acceptance of the beautiful woman, and ultimately, a consummation of his frustrated desires. This never happens in these stories, however (though Lois will occasionally steal a kiss from Superman, he is sure to stop matters there). Instead, the “wish” that seems to be granted is the assertion of power over women, in which they become a toy to be played with, mocked, and manipulated, as “revenge” for failing to notice the “super” qualities hidden underneath the modest, weak, and introverted exterior (qualities which, of course, may not exist for Superman’s real-life readers and counterparts). In the wishes “fulfilled” by Superman, it appears that love, companionship, acceptance, and even heteronormative sexual fulfillment are never that which the creators and readers really desire. Rather, what they want is simply “power,” and “power” is equivalent to “power over women.”

Rather than positioning this as a kind of simplistic accusation against the creators themselves, both now deceased, or even against the readers who consumed their stories, we can perhaps see how the scenario is not unique or idiosyncratic, but is in some ways typical of patriarchal societies, revealing important facets about how they (still, to some degree) function. As feminist/queer theorist Eve Sedgwick has discussed, stories that revolve around love triangles are not only common, but can be used to uncover the structures and psychologies behind both misogyny and homophobia. Following René Girard’s study of ‘erotic triangles’ in Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, Sedgwick notes that stories about “love triangles” (and particularly love triangles involving two men and one woman) are rarely ultimately concerned with the “relationship” between either man and the woman involved, but are more often preoccupied with the “homosocial desire” between the two men. In this, Sedgwick also constructs her argument around Gayle Rubin’s well-known claim in ‘The Traffic in Women,’ that the important relationships in patriarchal society are historically “between men,” as it is within those relationships that power is typically acquired and/or transacted. Women are traded (often in marriage) as a means of sealing social bonds between men, with the resultant male offspring inheriting the power gained through the union of the two patriarchs. Marriage as an institution, in this view, evolves not out of heterosexual “love” or even heterosexual desire but out of the ways in which clans, tribes, families, or societies secure what Sedgwick calls “homosocial” bonds. While it is obviously the case that women are no longer legally identified as commodities or traded between men, these attitudes remain present in our society and are worth interrogating. Rubin, for instance, notes that the practice of a father “giving away” his daughter at a wedding is a relic of these practices that is still often uncritically practiced.

Sedgwick’s rereading of Rubin (itself something of a rereading of Claude Levi-Strauss’ account of kinship structures) then focuses on the ways in which the ‘traffic in women’ is not only a model by which women are “objectified” as commodities to be traded, but by which same-sex male desire is expressed, ‘triangulated’ through women. That is, the woman in the “middle” of a love triangle serves as the transient repository for the “desires” the men actually feel for each other (social, economic, and/or sexual) (Between 21). This desire is “homosocial” (not strictly “homosexual”) because it does not necessarily involve any explicitly expressed sexual desire. At the same time, Sedgwick argues that the supposed distinction between homosexual and homosocial desire is not as solid as societies pretend. Rather, it is part of a fluid ‘continuum’ wherein social/economic bonds slide into, or blur into, sexual ones (Between 3-5). For her (and for Rubin), the institution of marriage, and the role of reproduction in sealing social and economic bonds leads not only to the objectification of women, but also to homophobia, since the line between the homosocial and the homosexual must be, and is, heavily policed. If the ‘traffic in women’ is so important to the sealing of bonds “between men,” then it is dangerous for such triangulation of desire to be circumvented in favor of a direct homosexual connection. Homophobia is then a logical result of a patriarchal/homosocial society wherein power is sealed through the trade in women as commodities. Rubin argues that, ‘The suppression of the homosexual component of human sexuality, and by corollary the repression of homosexuals, is…a product of the same system whose rules and relations oppress women’ (Rubin 180). For Sedgwick, then, homoeroticism is a repressed but constant presence in patriarchal societies because it both facilitates homosocial bonds and threatens them. The lingering homophobia in our own culture (and certainly that present in the 1930’s-1940’s America of these Superman comics), then, can also be seen as a signifier of the still powerful structures of patriarchy and misogyny.

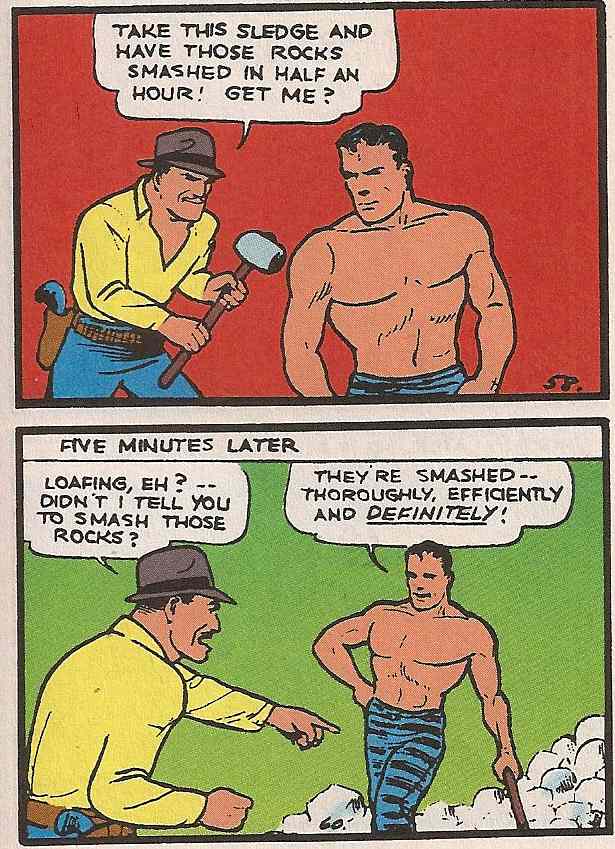

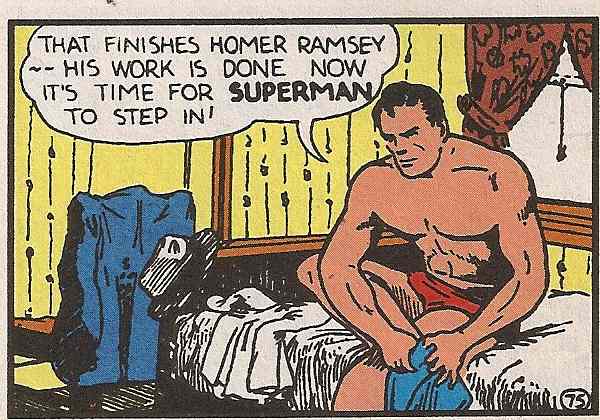

The claim that there is a “latent” homoeroticism in superhero comics is hardly a new one, going back at least as far as Fredric Wertham’s homophobic attacks in Seduction of the Innocent (1954). Certainly, the frequently aired claim that the “secret identity” is a metaphor for a “closeted” homosexuality is useful and worth examining more fully as long as it is not deployed in a pejorative fashion, as Wertham does. In the context of Siegel and Shuster’s Superman, some version of homoeroticism is easily observed, as these comics linger on the idealized male body (often half-nude) with some frequency, despite their principally male, and presumed straight, audience. Joe Shuster’s personal fascination with bodybuilding culture (see Jones 69-70) is evident in these homoerotic stories, as is the whole genre’s interest in idealized masculinity, or the ‘beauty of the male human body’ (Jones 75). Still, as Sedgwick might suggest, in Superman this “desire” never veers into the explicitly sexual (how could it in the homophobic America of the ‘30s and ‘40s?), instead “repressing” it in favor of a homosocial bond triangulated through a woman. In this, it is possible, along with Sedgwick, to see the (barely) concealed homoeroticism as that which facilitates misogyny and the objectification of women, as well as homophobia itself.

The strange Clark/Lois/Superman love triangle can be understood in this context despite the fact that the two men involved are actually one. As in Sedgwick’s model, in this triangle, it is less important for sexual desire (whether hetero- or homo-) to be satisfied, than it is for male power to be (re)asserted, with Lois becoming the ‘object of exchange’ (Between 26) between the “two” men. Within these stories, it seems, Lois’ desire for Superman must never be realized simply because the desire is so obviously hers, an assertion of female agency that patriarchal society must subjugate, control, and redirect for its own purposes.

On some level, certainly, Lois represents the shift in American gender roles in the wake of women’s suffrage post-1920. Lois is a strong-willed woman, operating with a job in the public sphere, often beating Kent to stories and even acting against the will of her superiors at the newspaper in pursuit of her professional advancement. At the same time, Lois is continually placed in the role of a submissive dependent, “saved” by Superman from innumerable toughs, bad guys, and natural disasters, indicating, perhaps, that her assertion of “subjectivity” is overstated, allowed by male patriarchal society only insofar as it is a result of its protection. Similarly, her agency in the private arena of love and sexuality is depicted, literally, as a joke, secretly laughed at by Kent (and therefore by Superman) as simply the game he/they play(s). Far from a queen on the chessboard of these comics, she is a pawn manipulated by the two men who are actually one. In all of this, the early Superman stories both acknowledge and illustrate the shifting position of women in American society and attempt to recuperate male power by suggesting that newfound female agency is carried out only as a result of (Super)man’s largesse and power, not in spite of it.

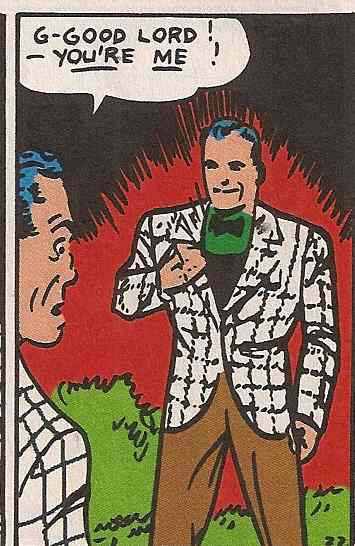

One of the earliest Superman stories, in Action Comics #4, depicts a reflection of Sedgwick’s scenario in an only slightly displaced context. A mediocre football player, Tommy Burke, is dumped by his girlfriend, Mary (who looks quite a bit like Lois), for never living up to his promise of stardom. Meanwhile, Superman, in order to foil the plans of some gangsters, steps into Tommy’s shoes on the football field (Tommy, drugged by Superman, is kept out of the way for the duration). After playing most of one game as Tommy (becoming the star the real Tommy never was, and thereby foiling the gangsters’ efforts), Superman quickly allows Tommy to resume his real identity, his recent stardom predictably delivering Mary back into his arms. As in the typical Clark/Lois/Superman triangle, two men play one, though in this case, the ‘traffic in women’ is literally completed, with one version of Tommy (Superman) delivering Mary into the hands of another, sealing the short-lived homosocial bond between them (Tommy happily “forgives” Superman for knocking him out and replacing him). Mary, of course, believes that she has “chosen” to return to Tommy, but, in fact, she is manipulated into doing so, the object of a transaction “between men.”

Of course, in this case, there are literally two men (although, through Superman’s disguise, they are indistinguishable), while in the more consistent triangle in Superman, two of the men are actually one. For this reason, it might be easy to say that there is nothing “homoerotic” or “homosocial” about the Clark/Superman/Lois triangle. Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, and legions of adolescents in similar circumstances don’t “desire” Superman, but rather desire “to be” him. In the welding of Clark Kent to Superman, this desire is achieved, though, of course, the realization of this desire is always simply a matter of fantasy. Despite Joe Shuster’s weightlifting and bodybuilding, he never can actually become Superman, just as any “real life” Clark Kent cannot. In this way, Superman is always both a realized desire and a frustrated one.

Likewise, the desire for power here may be read as a sexual, or erotic, desire. In Epistemology of the Closet Sedgwick makes the case that the desire ‘to be’ someone is not so easily removed from the simple desire ‘for’ someone. In fact, she states this, (perhaps not so) coincidentally, through a reading of Nietzsche’s work, particularly in Thus Spake Zarathustra, wherein Nietzsche expresses a desire ‘to be’ Zarathustra, ‘to be’ the übermensch, and thus ‘to be’ Superman. Segwick configures this explicitly as a homoerotic/homosocial desire by Nietzsche ‘for’ Zarathustra (for the übermensch, for Superman), which is then occluded or repressed by the language of ‘identity’ instead of desire (162). The results, as discussed in Between Men, are homophobia and misogyny. The desire to “transcend man” or to be the “super man” is also and always the desire for the superman, argues Sedgwick, as well as the desire to have power, which is itself the desire for power over women.

Indeed, the melding of two points of the love triangle into one accomplished by the “dual identity” of Superman and Clark speaks to a kind of desire for omnipotence that goes beyond a simple reflection of the workings of ordinary patriarchy. Rather, a desire is expressed to occupy both sides of a typical patriarchal transaction, as Clark and Superman, the “ideal man,” can be both the “seller” of women and their “buyer,” never having to make a “deal” or transaction with another man in order to consolidate power. Instead Clark/Superman, despite his left-leaning beginnings, simply makes deals with himself in a kind of monopoly capitalism where Lois (and women more broadly conceived) are the commodities not so much traded between tribes, families, or companies as circulated within the various subsidiaries of the single company.

In Men of Tomorrow, Gerard Jones describes a story Jerry Siegel submitted in 1940, after marrying his first wife, Bella, wherein Superman would be made vulnerable by a ‘K-metal’ (later to be used a Kryptonite) and would reveal his secret identity to Lois, dissolving the long-lived triangle and allowing her to become a ‘confederate’ in his battle against crime (qtd. in Jones 182). Lois makes explicit her movement away from the role of pawn, victim, and commodity in the story, when she declares, ‘Then it’s settled! We’re to be—partners!…Yes partners!’ (qtd. Jones 182). Even by this early date, however, Siegel was losing artistic control over his creation, and his editors rejected the proposal, insisting that Lois’ deception and the triangle established in the comics’ earliest days were essential to the Superman concept. Female agency and some measure of equality is literally proposed by Siegel, but is summarily rejected by those (men) who see the fantasy of male power as inextricable from the deception of women and female disempowerment.

While there have been shifts in the portrayal of Lois in the comics over the years (including a period wherein she was the protagonist in her own comic, and another where she is actually married to Superman), superhero stories both in comics and in broader media continue to follow the DC editors’ lead, in many cases. Christopher Nolan’s 2005 Batman film, The Dark Knight, for instance, revolves around a love triangle between Bruce Wayne/Batman, Harvey Dent/Two-Face, and Rachel Dawes. Eventually kidnapped and killed, despite having a prominent role in two films as Bruce Wayne’s best friend and potential paramour, Rachel is eventually reduced to the female “object” that facilitates the homosocial connection between Wayne and Dent. Similarly, 2011’s X-Men: First-Class revolves around a love triangle that positions Raven/Mystique between Professor X and Magneto, serving as the “object” that helps define the relationship that is clearly most important in the film, the homosocial competition/friendship between the two men. 2012’s The Avengers, while without a typical love triangle, depicts a transparently homosocial environment, wherein all the important heroes (and characters) are men, with the lone superheroine playing the role of objectified window-dressing, despite her occasional assertions of physical prowess.

While there is nothing intrinsically wrong with stories about relationships between men, of course, these films retain the basic structure Sedgwick identifies as facilitating both misogyny and homophobia. These female characters, though occasionally strong in their own right, function in their stories as mere conduits for the “important” relationships between men, and those relationships themselves are part of the process of defining power and wish-fulfillment. Likewise, in accordance with Sedgwick’s claims about the link between misogyny and homophobia, the relationships between men in these films are never allowed to veer into the realm of the frankly homosexual.

Seventy-five years after Superman’s introduction in Action, it remains rare to see depictions of (super)power that are not tied into misogynist conceptions of “power over women,” while simultaneously channeling male homosocial desire away from the homosexual. This type of “power” is itself linked to the “love triangle” plot structure hardly original to early Superman comics, but essential to them. Identifying this tie, whether in the genre’s origins, or its more current examples, is necessary, if it is to be broken and re-envisioned. While we live in a world stumbling slowly toward gender equality and the acceptance of non-heteronormative sexual orientations, our heroes, and their stories, should reflect such progress, rather than mirroring their troubling, and triangular, origins. While the early issues of Action are hardly intended as serious social commentary and retain a certain naïve charm that contemporary superhero comics are often lacking, they also stand as an example of the ways in which American culture then, and even now, configure (male) power as the power to trade in women, an example it is best not to follow.

Works Cited

Daniels, Les. Superman: The Golden Age. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1999.

Jones, Gerard. Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book. New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Kurtzman, Harvey and Wallace Wood. ‘Superduperman.’ Mad for Decades. New York: Metro Books, 2007. Reprint from MAD #4, April-May 1953. 1-8.

Rubin, Gayle. ‘The Traffic in Women: Notes Toward a Political Economy of Sex.’ Toward an Anthropology of Women. Ed. Rayna Reiter. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1975. 157-210.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia UP, 1985.

___. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: U of California P, 1990.

Siegel, Jerry and Joe Shuster. Superman Chronicles, Volume 1. New York: DC Comics, 2006. Reprints Superman stories from Action Comics #1-13, Superman #1, and New York World’s Fair #1, dated June 1938-July 1939. All images of Superman from this text.

___. ‘“Jerry and I Did A Comic Book Together…”: Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster Interviewed.’ 20th Century Danny Boy. 3 August 2012. Reprint from Nemo: The Classic Comics Library 2 (August 1983). http://ohdannyboy.blogspot.com/2012/08/jerry-and-i-did-comic-book-together.html.

Eric Berlatsky is Associate Professor of English at Florida Atlantic University. He is also the author of The Real, The True, and The Told: Postmodern Historical Narrative And The Ethics of Representation (The Ohio State University Press, 2011) and the editor of Alan Moore: Conversations (University Press of Mississippi, 2012). The Real, The True, and The Told explores the intersections of postmodern theory, narrative theory, historiographic theory, and contemporary fiction (and comics). Articles on similar topics in The Journal of Narrative Theory, Cultural Critique, and Virginia Woolf: Across the Generations preceded the book. Alan Moore: Conversations is a collection of interviews with the co-creator of Watchmen, V for Vendetta, From Hell, and Lost Girls. Berlatsky is at work on a critical volume devoted to Moore’s work and has an article forthcoming on pop music and the writings of Hanif Kureishi. He has also published articles on sexual perversion in Julian Barnes’ Flaubert’s Parrot (in Twentieth-Century Literature), narrative frames (in Narrative), and race in Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy (in The Arizona Quarterly). He teaches twentieth century British literature, literary theory, postcolonial literature, postmodern literature, and comics.

[1] – In a probably irrelevant coincidence, Siegel and Shuster were themselves involved in a love triangle, with their own “Lois.” Joanne Carter (born Jolan Kovacs) was the teenage girl who served as Joe Shuster’s model for Lois Lane, leading to a brief romance and a lengthy correspondence. Upon being reunited with Carter at a party she attended with Shuster in 1947, Siegel was smitten and ‘Joe stepped aside’ (Jones 248), leading to her eventual marriage to Jerry. See Jones (248-49) and the Nemo interview listed below, in which Joanne participated.

Kentarou

2016/03/30 at 09:36

When a man is obsessed with homosexuality we know he isn’t heterosexual. He’s fighting same-sex attraction and trying to align with what society says about men: “you must like women”. So he feels the need to present himself in exaggerated masculine ways (hyper-masculinity).

I’m not saying anything new here, it’s called repressed same-sex attraction. Every year since 1996 studies have shown that most homophobes are repressing same-sex attraction.

I see this in bodybuilding all the time. The amount of repressed men in bodybuilding both as bodybuilders and fans together could form a small country themselves. Where do you think they homophobia comes from? Their own fears of their own feelings not being what society expects of them.

LikeLike