It will come as no surprise to anyone reading this that comics has a massive arsenal of techniques for the representation of violence, of trauma, of horror, of life. Indeed, the array is so vast that this paper can only concentrate on a single technique – one that is both subtle and incredibly effective. This is a technique that allows violence to be implicit. It is sneakiness and cleverness combined. It is, to my mind, one of the best examples of the utter magic of the comics form. I am talking about the representation of the human eye. It may not seem at first that the drawing of an eye is anything more than just that – an eye. But I propose that the way an eye is drawn and its relationship to the rest of the image is in fact an acutely important representational tool and one that allows violence to be implicit, dependent on the reader’s imagination.

In this paper, I consider examples from two American war comics. The first is Doug Murray and Mike Golden’s The ‘Nam, a Marvel publication that ran from 1986 to 1993 that mimicked the typical tour of duty so the characters were rotated in and out of story arcs as they would have been in combat. The series followed the Comics Code Authority guidelines and as such does not depict certain aspects of the Vietnam War – no drug use, no swearing. That said, it does have a fairly level approach to combat and is rightly praised for not subscribing to the ‘men’s adventure’ derring-do style storytelling that is has been employed by other publications. The second example is Blazing Combat, written by Archie Goodwin, which ran from 1965 to 66 before being rather abruptly cancelled. The second issue ran a story set in Vietnam and this was something of a death knell. American PX shops (shops set up on American military bases internationally) refused to stock it because, while the comic is not necessarily anti-war, it steadfastly refuses to subscribe to any glorification of war and instead concentrates on individuals and the trauma of their experience. These are not typical war comics – neither are as brash as Commando or Battle. As Kurt Vonnegut would suggest there is no role for John Wayne here (see Slaughterhouse-Five, p.11).

So what am I proposing about eyes? I propose that the shape of the eye in the examples I discuss here act as a frame-within-a-frame. Most panel frame shapes are easily recognisable to us. Wavy edges suggest a dream or an altered conscious state (drunk, perhaps), sharp pointed edges show an explosion or a loud noise. A straight-edged rectangular frame shows us that what is contained is happening in the present. Will Eisner considers these to be ‘container frames’ and further suggests that as comics readers we read (or should read) the shape of the frame as much as any other part of the image. He suggests that panels are an excellent way for the comics creator to control the reader and construct the grammar of the comic itself. He writes:

The intent of the frame [can be] not so much to provide a stage as to heighten the readers involvement with the narrative. [. . .] Whereas the conventional container-frame keeps the reader at bay – or out of the picture, so to speak – the frame can also invite the reader into the action (2008: 46).

In the case of my examples the eye is the only contained space within the image and so becomes a double frame. It is another framing shape that we must read in order to gauge the action and the direction of the narrative.

We humans are a surprisingly predictable species and we are programmed (for the most part) to look at the face of an individual for confirmation of their mood and personal state; the expression within a person’s eyes plays a large role in this evaluation (for a recent and comprehensive study to this effect see Eisenbarth and Alpers, ‘Happy Mouth and Sad Eyes: Scanning Emotional Facial Expressions’ in Emotion, 2011). Therefore it does not seem unusual that the eyes of a character would need to be the most expressive part of their face, nor that using the eyes to display emotion has become a trope in visual narrative arts. However, I wish to take this further. Not only are the eyes the most expressive part of the face, but they remove the need for the violence of the situation to be visually represented within the panel. The expression in the eyes is enough to imply the violence that that particular character is witnessing. We can clearly read the violence in the face of the character and we do this through the eye. In each example I discuss, the eye forms the central focus of the panel and it is through the eye that the mood of the panel and thus the mood of the character is conveyed. After a close reading of the panel, I take the issue further and consider the wider implications of implied violence.

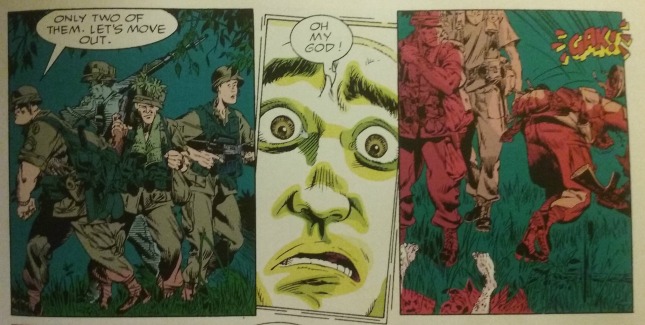

My first example comes from the first issue of The ‘Nam (1986). Private Ed Marks has just arrived in Vietnam and is immediately thrown into combat. He witnesses an attack on a small village and sees many men killed in front of him. This panel is his reaction to that which is going on around him. Bear in mind that because of its adherence to the Comics Code Authority rules, the majority of violence is not horribly graphic and gory in The ‘Nam. Ed’s reaction is designed to convey this to us without the need for graphic gore. The overall panel is tilted on the page, overlapping with the panels either side.

Initially, just by reading the outer panel we get a sense of chaos. The coloration is unusual – a greenish colour highlighting the whiteness of Ed’s face. His mouth is contorted. His eyes, however, are clear and wide. We are in no doubt as to the expression in his eyes. This is shock and horror on a grand scale. We are used to the expression ‘wide eyed’ in horror, in surprise, in whatever. Ed’s eyes really are. I don’t suppose we usually give it much thought but it is unusual to see the whole of the pupil of an eye surrounded with white like that. What is crucial to this reading of the eye as being indicative of a wider implied violence is that they can stand alone on the page and still convey the same message.

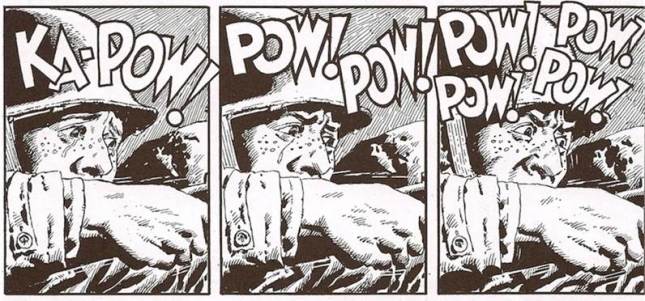

My second example comes from the Blazing Combat story ‘Holding Action’. This short comic is set in 1953, during the Korean War. A young soldier, Stewart, is part of a group attacked by Korean forces. He tries to hide but his commanding officer calls him a coward and forces him to shoot at the enemy soldiers. These three panels are all that we see of the attack going on around him as he shoots. It is clear that, aside from in basic training, Stewart has never fired his gun. The expression in his eyes shifts from pure terror and shock to angry determination and fear. With the exception of the onomatopoeia above him, the eyes are the only thing that changes in the three images. More so than with the image of Ed Marks, the eyes of Stewart are essential in the understanding of the situation. Stewart becomes so consumed by the violence all around him that he seems to forget his fear and his reluctance to shoot at other human beings and instead becomes incensed with his attempts to kill them. However, it is only because we can read this change in his eyes that we see that this shift is taking place. Without the shifts in the shape of the eye this change would not be communicated – or it would require some fairly clunky speech or thought bubbles. The eye allows the shift to be seamless.

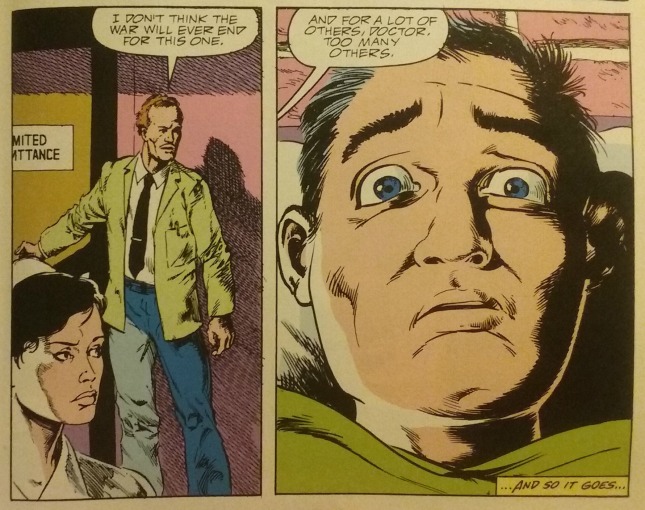

Finally, I present another from The ‘Nam. The character is Frank Verzyl. A former soldier and tunnel rat (someone who goes into the Viet Cong tunnels to help destroy the network from within), he is attacked by rats which triggers a serious psychotic break, leading him to kill the commanding officer. He is returned to the US and confined in a psychiatric hospital. Within The ‘Nam, Verzyl becomes a figurehead for those soldiers for whom the trauma became so completely unbearable it leads to total mental breakdown and a collapse of basic bodily functioning.

As we saw with Ed’s eyes, there is a lot of eye white on show. Verzyl’s eyes are wide in terror, just as Ed’s were. The difference is that Ed was witnessing live combat and his expression was consistent with what was passing in front of his eyes. Verzyl is in a hospital – he is to all intents and purposes safe. The terror he is witnessing is that which his traumatised mind is playing on a loop without comprehension. He is trapped in that moment and the terror in his eyes is the terror of a trapped, traumatised man.

I suggest that violence is, by its very nature, traumatic. However, we have become strangely desensitised to representations of violence in a way that we have not with trauma. Thus, it is in the representation of the trauma of violence, rather than the violence itself that the true power of these comics is felt. Violence is universal but trauma is uniquely human and its displays are more likely to stir something in us. It is when we begin to consider trauma that the difference between seeing and understanding becomes heightened. Trauma is about witnessing – seeing – an event so mind-blowing and life-altering and life-threatening that the mind is unable to understand it. And it is this lack of understanding and lack of assimilation that causes the trauma. This event exists in the mind of the individual but they have no way of assimilating it into their memory, as Cathy Caruth contends (see Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative and History, 1996); they cannot process what they have seen and it becomes a non-event. Seen but not understood. Witnessed but not comprehended. As an aside, trauma and seeing are so entwined that the Dutch Guide Dogs Charity now also supply trauma dogs for returning servicemen. Their strapline is ‘For those who cannot see and those who have seen too much’. Trauma and seeing are very closely related and so it is only fitting that the eye becomes the focus.

The specific structural and artistic techniques of comics are able to mimic the symptoms of a traumatic rupture caused by witnessing extreme violence in the representation of the character’s eyes. We as readers are invested in the creation of the unseen violence by the way in which we read the eye, which in turn goes some way to mimicking the experience of a traumatic rupture in the reader. It is by considering the trauma that violence engenders – rather than violence alone – that these comics make a statement about the nature of conflict violence. Were they to present the violent events in a gung-ho fashion, suggesting all manner of glory and marvel for the participants, we would learn nothing. Instead, seeing the true terror of violent action – and the horrible effects it can have on the human condition – we begin to get a more accurate picture of the extent to which conflict violence affects its participants and, by extension, us.

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative and History. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Eisenbarth and Alpers, ‘Happy Mouth and Sad Eyes: Scanning Emotional Facial Expressions’. Emotion 11 (4) August 2011. pp 860-875.

Eisner, Will. Comics and Sequential Art. New York: Norton, 2008.

Goodwin, Archie et al. ‘Holding Action’. Blazing Combat. New York: Warren, 1966.

Murray, Doug and Mike Golden. ‘First Patrol’. The ‘Nam. New York: Marvel, 1986.

. – ‘Auld Acquaintance’ The ‘Nam. New York: Marvel, 1989.

Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. London: Vintage, 1991.

Dr Harriet Earle has recently completed her PhD in American Comics at Keele University. She is currently preparing her first monograph on the topic of comics and conflict trauma. Her publications are spread across the field of comics studies and in the future she hopes to continue working on traumatic representation in comics, literature and art.