Christian A. Bachmann

This article is the first part of a short series that deals with the representation of music and musicians in cartoons and early comics. European magazines such as Charivari (Paris), Punch (London), and Fliegende Blätter (Munich) published caricatures and picture stories about the virtues of music and her practitioners throughout the 19th century and beyond. Preoccupied with making their readers laugh, artists such as Grandville or Wilhelm Busch have often depicted the failing musical aspirant who makes his instrument and his audience churn. The rise of and constant debate about Wagnerian ‘modern music’ spurred the idea of oversized instruments, powered by steam engines that, accordingly, made the very same noise rather than delightful music. With the ascent of Franz Liszt and other virtuoso musicians in the 1830s and 1840s, a new stereotype entered the stage of the satirical magazines. The ideas, characters, motifs, and techniques developed for representing music and musicians were by no means limited to Europe, but also carried over to the United States where they were adapted for an American magazine readership and became part of the ideas and techniques on which the early newspaper comics were based. Unsurprisingly, because artists like Frederick Burr Opper and Frank M. Howarth, both of whom drew pictures stories about musicians, started out with their careers in US-magazines like Puck and Judge, before moving on to work for the newspaper industry around the turn of the century.

This series of articles comprises three case studies that reconstruct some of the notions that were carried through the 19th century and ended up in comics where they can partially still be found today. The articles are shorter versions of some of the (sub-)chapters of a book-length study that will come out in German later this summer. This study is based on a corpus of roughly 600 caricatures, picture stories, and comics printed between 1830 and 1930, with brief glances at earlier works like William Hogarth’s engraving The Enraged Musician and later publications such as Air Pirates Funnies. The first case study deals with the ‘Power’ of Music and its assumed ‘charms’. The second presents the development of the virtuoso stereotype from Grandville to Outcault. Finally, the third showcases a special kind of graphic narrative that Lothar Meggendorfer has termed ‘Notenscherz‘ (‘musical note-gag’).

NB: Please contact the author if you would like to access the corpus.

Part I: ‘Music hath charms’

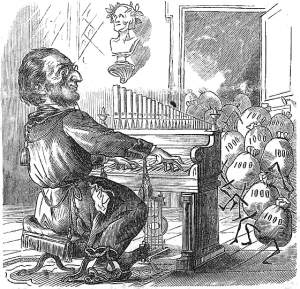

It is widely believed that music has power of humans and animals alike, sometimes even over the realm of the inanimate. This notion has its roots in Greek and Roman antiquity, but might very well go even further back. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid tells us how Orpheus reached out to the gods by singing and playing the lyre. So touched were the gods that they allowed him to descend to the underworld from where he would almost return with his beloved late wife Eurydice. And in Horace’s De Arte Poetica we read of Amphion, son of Zeus, who helped build Thebes by means of his musical prowess. While Amphion is a second-tier character from Greek mythology, Orpheus is very well known to this day and his story is told over and over again in literature and on stage. Caricature and comics too have often called upon Orpheus. Take, for instance, this caricature of Richard Wagner subtitled ‘Der alte Orpheus setzte Felsbrocken in Bewegung, der neue lockte Metallstücke an. Und noch dazu nach einer unendlichen Melodie!’ (‘The old Orpheus moved Rocks, whereas this new one lures pieces of metal. And, on top of that, with a never-ending melody.’) Published in 1865 by Martin Eduard Schleich in the Munich-based satirical magazine Münchener Punsch, this caricature—one of many about Wagner—puts the musician into the place of Orpheus, poking fun at the generous financial support Wagner received from Ludwig II of Bavaria at the time.

Fig. 1: Martin Eduard Schleich in Münchener Punsch (1865). Image is in the Public Domain.

Through time the notion of the ‘Power of Music’ has become a staple in Western thinking. Not only is there ongoing research on the effect that music has on the human body and cognition (e.g. Trappe/Voit 2016), the ‘Power of Music’ is, indeed, so common a metaphor in many European languages (‘pouvoir de la musique’, ‘Macht der Musik’) that we hardly think about it at all. For cartoonists of the 19th and early 20th century, music and musicians have been a popular choice for a light-hearted jest as well as some edgy visual commentary on developments in music and society. Although many examples could be given, a few must suffice at this point. In 1885, Lothar Meggendorfer, the famous German illustrator and designer of movable books, published not one, but two picture stories titled ‘Die Macht der Musik’ (‘The Power of Music’). Both were printed in the Fliegende Blätter, a weekly satirical magazine based in Munich. The first picture story (fig. 2) consists of four panels that tell (or show) how an unsuspecting seaman is sneaked upon by a lion. It is by the power of his accordion that the sailor can fend of the beast. The joke here lies not only in the music produced with this particular instrument being so unpleasant that it scares off the animal, but also in the stretched out accordion mirroring a lion’s gaping jaws.

Fig. 2: Lothar Meggendorfer, ‘Die Macht der Musik’ (‘The Power of Music’) in Fliegende Blätter (1885). Image is in the Public Domain.

Meggendorfer’s second picture story of the same title and the same year tells the story of a violin player who entertains a military officer. The story is structured in two halves that roughly correspond with the Aristotelian notion of catharsis. In the first half, the musician plays something sad, making the officer cry. Afterwards, he plays something jauntier, enticing the officer to dance vividly. The officer’s handkerchief—know from Wilhelm Busch’s ‘The Virtuoso’, about which more in the second part of this series of articles—, earlier used to wipe away the tears, now soaks up his sweat (fig. 3)

Fig. 3: Lothar Meggendorfer, ‘Die Macht der Musik’ (‘The Power of Music’) in Fliegende Blätter (1885). Image is in the Public Domain.

William Congreve’s play The Mourning Bride (1697) has been instrumental in establishing the metaphor of the ‘Power of Music’. ‘Music has Charms to soothe a savage Breast, / To soften Rocks, or bend a knotted Oak. I’ve read that Things inanimate have mov’d, And, as with living Souls, have been inform’d, By magic Numbers and persuasive Sound,’ cries Almeria in mourning. While Congreve’s play has mostly been forgotten, it is this line—’Music has Charms’—, that has since become a proverb, that helped carry over the metaphor of the power of music from antiquity to the modern day. In this form it shows up in a number of American comics. And even more so in the modified phrasing ‘Music has Charms to soothe a savage Beast’, which can be combined with the power attributed to Orpheus. The Welsh artist John Samuel Pughe presents us with a modernized Orpheus in a picture story published in Puck in 1898. Titled ‘Die Macht der Hypnose’ (‘The Power of Hypnosis’) in the German edition of the New York magazine the story tells yet again of a lion tamed by its human prey (fig. 4)

Fig. 4: Samuel Pughe, ‘Die Macht der Hypnose’ (‘The Power of Hypnosis’) in New York Magazine (1898). Image is in the Public Domain.

The human protagonist, a magician named Singali, pejoratively called ‘Operetten-Fabrikant’ (‘manufactor of operettas’), whom Pughe draws in accordance with the virtuoso stereotype, chances upon a lion: ‘Als fern ein Löwe brüllt und heult. / Singali traut kaum seinen Sinnen / Und ruft: ‘Den Baß muß ich gewinnen!’ (‘When far a lion growls and howls. / Singali, he his senses doubts, / cries: ‘This bass now I must seize!’). Thus, he prepares to capture the lion. However, he does not operate with Orphic singing and lyre play, but with hypnosis that was a popular topic in the late 1800s. The trick succeeds and back in New York Singali can present the lion, now dressed as a stereotypical virtuoso and playing on the banjo, to the cheering audience of an opera house. To subdue the lion, Singali has to become lion-like himself, before the lion becomes anthropomorphized in the last panel. Comic artists, we must assume, knew these stereotypes.

Another example of the soothing charms of music can be seen in an episode of Charles H. Wellington’s comic strip ‘Say!! Did this Ever Happen to You??’ published in 1905 (fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Charles H. Wellington, ‘Say!! Did this Ever Happen to You??’ (1905). Image is in the Public Domain.

In this strip, an amateur piano player sings and plays for a major who is paying her a visit. Through her play and incantation of Will D. Cobb’s and Gus Edwards’s 1902 song ‘Could You Be True to Eyes of Blue (If You Looked into Eyes of Brown)’ the elderly Major falls fast asleep. His snoring, however, puts her off the music and offends her deeply. It is noteworthy that Wellington combines a number of elements, semiotic as well as cultural, that can be found in many comic representations of music and musicians. Beginning with the technological improvements of the piano in the early 1800s, this instrument spread to middle class households all over Europe and the United States in what, at the time, was derided as the ‘piano craze’. Many a bourgeois girl in her teens learned to play the piano at home, and there were plenty of caricatures and comic stories that ridiculed this practice and the nuisance it meant to neighbours. Wellington’s girl, who appears to be the offspring of a well-to-do household, is a late successor of these young women. The bust that Wellington placed on the piano, too, has its paragons in earlier picture stories that feature similar anthropomorphized busts appalled by the incompetence of the amateur musician. And, lastly, it should be noted that the way Wellington depicts the musical sounds themselves—which he does by means of musical notes that fly through the air—goes back at least to Grandville, who did so in the illustrations of his Un Autre Monde (1844).

The power of music is so universally present in culture that even Martians take note of it. At least, Mr. Skygack does, Armundo Dreisbach Condo’s alien protagonist from the comic strip of the same name. In 1907 Mr. Skygack encounters a woman playing the piano for the first time and reports home: ’Heard frenzied shrieks in dwelling — entered and found earth-being in agony of apprehension over change of season—was relieving agitation by pounding furniture — felt sorry for her’ (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Armundo Dreisbach (1907). Image is in the Public Domain.

Even played by the Martian himself, music doesn’t seem to unfold the acclaimed effects, as the episode ‘Music Hath No Charms for Adolf’ relates. Mr. Skygack, arguably the first alien lifeform in the comics, receives the advice to play music for Adolf, his antagonist: ‘Dit you ever try to soothe Adolf’s savage bosom mit music, Mr. Skygack? No? Vell, try it! Even der soul of a anglevorm iss moved mit melody.’ To accomplish this, the hapless alien choses the bass drum to calm Adolf. Adolf quickly resolves the noise disturbance in the common way American slap stick comic strips of the time handled such things (fig. 7).

Fig. 7: Armundo Dreisbach, ‘Music Hath No Charms for Adolf’ (1907). Image is in the Public Domain.

Thus, even the alien, who could meet with any number of strange occasion or occurrence to write home about, is caught up with by stories about music. It is apparent that music, its production, and effects are part of US-society of the time, and, thus, they must be scrutinized by the extra-terrestrial. Moreover, the alien lifeform allows Condo to comment on the norms and lifestyles of contemporary US-society by (pretending to) focussing it through the lens of one who is a complete stranger not only to the US but to earth as a whole, as Ron Miller (2016) has pointed out. In 1908, Skygack encounters three musicians with a tuba, a trumpet, and an oboe, performing on the street and is thoroughly confused by them: ’Saw three earth-beings of distinctive type — held strangely shaped objects to face, making sounds like oom-pah, oom-pah, taa-de-daa, and pee-lee-weely-weely-wee, the same probably being signals of approaching danger’. And, indeed, it must be said, that many musical instruments, especially the woodwinds and brass, have undergone a steady development in the 1800s that turned them from rather simple instruments into intricate devices, sometimes with wondrous valves and inscrutable systems of tubes, which is to say that, really, they did become ‘strangles shaped objects’ to the unprepared eye.

In the comics, too, the power of music is not limited to humans (and aliens) but encompasses the animal kingdom, as the variation of the quote from Congreve suggests. Accordingly, Harry Cornell Greening, tells at least three stories about Uncle George Washington Bings that touch on the subject. In one of them, published in 1906, Greening’s screwball character Bings, ‘the village storyteller’, is received in her sitting room by an American lady. Her cockatoo, shown in the back of the panel, is reason enough for Bings to relate a story, which he does over the next four panels. At one time, he tells, he was preyed upon by ‘a lot uv verocious animals’, a lion, a leopard, and a tiger—a set of animals that would not naturally hunt in unison, which is indicative of the nature of Bing’s story. To save himself, he continues, he clamed a tree, on which he found the nest of a lyre bird, whose tail feathers not only closely resembles the shape of the musical instrument the bird was named after, but actually works as such: ‘So I grabbed the mother lyre bird an’ twanged out the sweetest tune yeh ever heard an’ charmed them ravenous beasts. / Ab’ I stayed an’ helped bring up the family an’ rigged up a key board like a pianner an’ toured through the jungles givin’ the beasts afternoon concerts!’ The instrument that Greening shows Bings give a concert on in the fifth panel, reminds us of Athanasius Kircher’s ‘cat piano’ (Fig. 8), a contraption in which the lyre birds are held fast and ‘played’ upon. Judging by the little work Greening put into drawing the ‘lyre bird piano’, he didn’t care so much about the instrument as such, but about the gag that he could deliver with its help. Note Bings’s grandiose pose and gestures, which are those of a piano virtuoso (which I discuss further in the second part of this series of articles). Funnily enough, it is the cockatoo, an animal himself, who debunk Bings’s story in the last panel.

Fig. 8: Harry Cornell Greening, (1906). Image is in the Public Domain.

In a 1909 episode of his famous strip ‘Buster Brown’, Richard Felton Outcault tells yet another variation of the charming effect of music. In February 1908 Oucault sent Buster on a journey round the world with his uncle. After calling in the USA, India, and Europe, Buster visits Africa with a boatswain called Bill, in the Spring of 1909. In an episode titled ‘On Trek in Africa’ they chance upon a group of monkeys that sling coconuts at them. To fend them off, the seaman—a group that is often depicted with musical instruments as we have seen earlier—plays Ernest R. Ball and Dave Reed’s song ‘Love Me, and the World Is Mine’ (1906) on his accordion, because, as Bill let’s Buster and the readers know, ‘music hath charms’. Immediately, the monkeys are pacified and begin to dance (fig. 9).

Fig. 9: Richard Felton Outcault, ‘On Trek in Africa’ (1909). Image is in the Public Domain.

Only six episodes later do we find Bill and Buster amidst a group of children of one ‘Boogloo’ tribe. They too lend an audience to Bill’s playing, who, this time, performs Stephen Foster’s ‘Old Folks at Home’ (‘Way Down Upon the Swannee River’[1851]). The moral of the story as presented in the form of a letter by Buster in final panel, explains the intention of this particular episode of the comic strip: ’Resolved that ‘one touch of nature makes the whole world kin’, and good nature is the only kind that meets the response of kinship. A merry heart and a kind soul are the best equipment for the battle of life, for the kicker gets only kicks in return, while the smiling countenance is reflected in faces all along the way.’ It should be noted, however, that Outcault has Bill sing a song specifically known from the Minstrel shows in which the lyrical subject ‘longs’ for his home on a plantation, giving the strip an—albeit unintentional—racist and colonialist subtext. Some episodes later, Buster and Bill still tour the African continent, the boatswain performs in front of an audience of animals. While parrot, pelican, and Buster’s dog Tige, enjoy the music (‘Tell Me, Pretty Maiden’ from Jimmy Davis’ musical Florodora [1899], and ‘Razors in the Air’ [1880]), elephant Jumbo takes no liking to it. Thus, he tries to stop the nuisance by means of splashing water on the musician. Buster and Bill, however, catch the animal and punish him by subjecting him to even more music. Finally, Buster volunteers: ‘Resolved that musical instruments are instruments of torture most of the time, and we punished baby Jumbo for doing what all of us have wished to do, and would have done if we had had Jumbo’s nerve. We leave the porch and slam the door when Smith’s Phonograph is started up. We tear our hair while Jones’ little girl exercises the piano-wires and the loud pedal, and young Jenkins’ cornet-playing turns our thoughts to guns and dynamite. Still, Paderewski had to learn his art, Melba was once a little girl, and all the great composers must have worried their neighbours at first. Let us endure the ›practice‹. We must have music, and we can’t have roses without thorns.’ (Fig. 10) The virtuoso pianist Ignace Jan Paderewski had successfully toured the US in 1892/93 and was met with fame similar only to that Franz Liszt procured in Europe in the 1830s and 1840s. After stints in Europe, Australian opera singer Nellie Melba, one of the most renowned singers of her time, made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1893. Outcault, it is clear, did not only know the musical stars and popular songs of his time, he could also expect his audience to understand the references he made. Also, he knew the tradition of satirical commentary on the nuisances of music, as Buster’s closing words show. In another ‘Buster Brown’ episode, which I will highlight in the next part of this series of articles, Outcault also shows an understanding of musical theory.

Fig. 10: Richard Felton Outcault, (1909). Image is in the Public Domain.

The power of music, established in antiquity, is very much a common theme of caricatures and picture stories from the 1800s and can still be observed in the early comics, as the few examples given above have shown. It should come as no surprise at all that early comics artists should have observed what pictures their earlier peers drew, what stories they told, and what motifs and stereotypes they drew on. There are numerous more stories that go in the same general direction, e.g. by Charles William Kahles, William Steinigans , Gene Carr, and Walter R. Allman. While not referred to on a daily basis, the notion of the ‘power of music’ has become a staple in the early comics. And, as the two following articles will elaborate upon, it has remained a staple to this day.

Dr. Christian Bachmann was a research associate (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter) with the DFG-financed research project ‘Das Künstlerbuch als ästhetisches Experiment’ (The artist’s book as aesthetic experiment). He is a visiting lecturer (Lehrbeauftragter) with the Departments of Comparative Literature at Ruhr University Bochum and Saarland University, with ‘Literatur und Medienpraxis‘ at University Duisburg-Essen, and with the Department of Comparative Literature at University of Innsbruck, Austria. Christian has studied Comparative Literature and General Linguistics in Bochum and was promoted to Doctor of Comparative Literature in January 2015 with a doctoral thesis concerning the mediality and materiality of comics. He runs a publishing company focusing on literary studies, cultural studies, and comic book studies (www.christian-bachmann.de).

References

- Busch, Wilhelm: Ein Neujahrsconcert [= Der Virtuose]. In: Fliegende Blätter 43.1865, supplement.

- Condo, A. D.: Mr. Skygack, from Mars. In: The Day Book, 07.11.1907, n.p.

- Condo, A. D.: Mr. Skygack, from Mars. In: The Day Book, 01.09.1908, n.p.

- Condo, A. D.: Mr. Skygack, from Mars. Music Hath No Charms For Adolf. In: The Day Book, 20.01.1914, n.p.

- Congreve, William: The Mourning Bride. In: The Works of Mr. William Congreve. 3 Vols. Birmingham: Baskerville 1761, Vol. 3, p. 6–153.

- Grandville (i.e. Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard): Un autre monde. Transformations, Visions, Incarantions, Ascensions, Locomotions […]. Paris 1834.

- Greening, H. C.: Uncle George Washington Bings, The Village Story-Teller. In: The Evening Star, 25.03.1906, n.p.

- Horaz (i.e. Quintus Horatius Flaccus): De arte poetica / Das Buch von der Dichtkunst. Trans. a. ed. by Hans Färber and Wilhelm Schöne. In: Horaz: Sämtliche Werke. Lat. u. Dt. Neuausgabe. Munich 1967, p. 230–259.

- Meggendorfer, Lothar: Die Macht der Musik. In: Fliegende Blätter 82.1885, No. 2075, p. 142.

- Meggendorfer, Lothar: Die Macht der Musik. In: Fliegende Bkätter 83.1885, No. 2098, p. 118–119.

- Miller, Ron: Was Mr. Skygack the First Alien Character in Comics?, http://io9.gizmodo.com/was-mr-skygack-the-first-alien-character-in-comics-453576089 (12.03.2016).

- Outcault, Richard F.: Buster Brown »On Trek« in Africa. In: Omaha Sunday Bee, 02.05.1909, n.p.

- Outcault, Richard F.: Buster Brown and the Boogloo Babes. In: Omaha Sunday Bee, 13.06.1909, n.p.

- Outcault, Richard F.: Buster Brown’s Pets. In: Omaha Sunday Bee, 26.09.1909, n.p.

- Pughe, John S.: Die Macht der Hypnose. In: Puck 22.40, No. 1132 (01.06.1898), backcover.

- Schleich, Martin Eduard: Ein neuer Orpheus. In: Münchener Punsch 18.50 (10.12.1865), Cover.

- Trappe H.-J., Voit G.: The cardiovascular effect of musical genres—a randomized controlled study on the effect of compositions by W. A. Mozart, J. Strauss, and ABBA. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2016; 113: 347%u201352

- Wellington, C. H.: Say!! Did this Ever Happen to You?? In: The San Francisco Call, 10.09.1905.