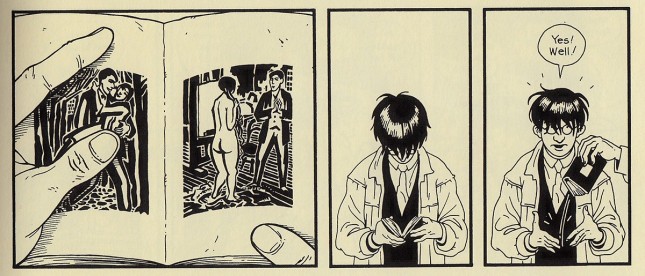

Jason Lutes’ stunning graphic novel, Berlin: City of Stones, captures a response to the woodcut novel that represents a common reaction by many readers who first open one of these books. In this case, the book Mein Stundenbuch (Passionate Journey) by Frans Masereel is targeted by the character Erich, who is having a heated discussion about objectivity and emotion with his friends. The panels display Erich as he pulls the book from his friend’s coat pocket. In a manner of disgust, Erich presents the book as an example of emotionalism. His attitude changes when he opens the pages and becomes engrossed in the pictures.

Erich’s interest reflects a natural desire for storytelling and in this example the power of woodcut novels, which are wordless imaginative and realistic stories by Masereel, Otto Nückel, Lynd Ward and others. They are told in black and white pictures that focus on humanistic ideas. The woodcut novel refers not only to woodcuts but also to wood engravings, linocuts, leadcuts, and solid plastic. A woodcut uses the plank cut with the grain, while a wood engraving uses hardwood cut across the grain that allows a finer line. Despite their short-lived popularity, the woodcut novel had an important impact on the development of the contemporary graphic novel.

The popularity of Masereel’s woodcut novel in this scene by Lutes, set in Germany during the 1920s, is due to the commitment of the publisher Kurt Wolff, who was introduced to Masereel’s woodcut novels by Hans (Giovanni) Mardersteig, Wolff’s book designer. Wolff noted his association with Masereel later in an essay:

It was Mardersteig who established the connection with Frans Masereel. When we first published his Stundenbuch (Book of Hours) in 167 woodcuts, the Belgian’s name was completely unknown in Germany. Within a few years Masereel’s series of woodcuts—Stundenbuch, Sonne (Sun), Passion eines Menschen (A Human Passion), Die Idee (The Idea), Geschichte ohne Worte (Story without Words)—produced in inexpensive editions with introductions by Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, and others, won a surprisingly large circle of admirers and attained a number of printings we had never expected, given the uncompromising quality and character of these books. (15) [1]

What made these books so popular? At the core of the woodcut novel and the wordless novel is the use of pictures to tell a story. In his critical book Words About Pictures, Perry Nodelman captures the essential ingredients of wordless novels.[2]

Because these books have no words to focus our attention on their meaningful or important narrative details, they require from us both close attention and a wide knowledge of the visual conventions that must be attended to before visual images can imply stories….finding a story in a sequence of pictures with no help but our eyes is something like doing a puzzle. It cannot be done if we do not know that it is meant to be done, so we must first understand that there is indeed a problem to be solved. (186-187)

In addition, a score of artists have found the woodcut novel a perfect medium to express their ideas from a personal, imaginative, and social standpoint. The process of carving a block is a ponderous activity with few practitioners today. Creators of the woodcut novels include George Walker and various artists who teeter between the graphic novel and artists’ books.[3]

Today, readers of comics approach the woodcut novel, and the wordless graphic novel in general, with a sophisticated graphic vocabulary, enhanced over the past two decades by the advances in technology and the greater use of an iconic language in various functions including smartphones, gaming, and, of course, the internet. Immediate access to information also provided answers to inquiries about the development of the graphic novel and artists of historical importance. The recognition of the woodcut novel as part of the medium of comics and its place in the history of comics was confirmed with the selection of Lynd Ward as the Judges’ Choice in the 2011 Will Eisner Hall of Fame.

This was not always the case. With little understanding or scholarly interest in this genre of storytelling these works remained in libraries, private collections, and used bookstores and were largely discovered serendipitously, as in my case. There were single editions of Masereel’s most important woodcut novel, Passionate Journey that Dover Publications (1971), Penguin (1988), and City Lights (1988) kept in print. Ward’s Gods’ Man was reprinted by World Publishing (1966), St. Martin’s Press (1978), and Abrams who collected all six woodcut novels, selected books illustrations and prints in Storyteller Without Words: The Wood Engravings of Lynd Ward (1974). The woodcut novels of Masereel and Ward were mentioned in books on illustration and printmaking but rarely from a narrative perspective. One scholarly article ‘The Novel in Woodcuts: A Handbook,’ published in 1977 by Martin Cohen drew little attention at the time but is now an essential work in the understanding of the woodcut novel.[4] When the comic book expanded from a serial to include a book length format referred to as a graphic novel, a term attributed to Will Eisner [5], the perception of the comic began to change.

It has been my advantage to witness the evolution of the comic that has also increased the awareness of wordless novels, my lifetime undertaking. The additional branding of the graphic novel and the sophisticated level of storytelling changed the public’s idea of comics, which created browsing areas in bookstores, and slowly opened the impenetrable golden gates of the Modern Language Association, so that graphic novels are now discussed at numerous conferences beyond the Comics Arts Conference, established in 1992, and the Popular Culture Association, which was the first national academic conference with a separate division devoted to comics scholarship.[6] Critical journals like INKS: Cartoon and Comic Art Studies (1994-1997) and International Journal of Comic Art (1999-) were established for a growing group of comic scholars and publishers like University Press of Mississippi—an early publisher of scholarly books on comics—are now among many journals and publishers devoted to comic studies. In addition, graphic novels are now taught at colleges and universities and are the subject of a growing number of dissertations.

Rosemary Ross Johnston joins others and me in recognizing the graphic novel as literature: ‘This reflects a significant and deeper shift in ideas about language in general, and about “reading” in particular. Images in narrative are no longer “viewed”; they are “read,” with all the implications that that term carries in the meaning-making process (422).’

Despite being considered oddities, woodcut novels were also being rediscovered and reported as a major influence in the lives of noted comic artists like Peter Kuper, wordless picture book artists like David Wisner,[7] and creators of artists’ books including Jules Remedios Faye. In addition, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and Will Eisner’s Graphic Storytelling were key reference books that identified the woodcut novel’s contribution in the development of comics.[8]

In conjunction with this growing public interest, Dover Publications came out with new editions of woodcut novels: five works by Masereel; Nückel’s masterpiece Destiny, which had not been republished since 1930; all six of Ward’s woodcut novels; and James Reid’s Life of Christ in Woodcuts. The Library of America chose Lynd Ward’s six woodcut novels as their first publication with illustrations in 2012, and an outstanding documentary film O Brother Man: The Art and Life of Lynd Ward by Michael Maglaras and Terri Templeton produced in 2012, that further affirmed public acknowledgment of the woodcut novel.

Earlier, when I was writing introductions to new editions of these forgotten woodcut novels for Dover Publications, I slowly discovered a rising fountain of wordless novels that surged with freshness and showered me with entirely new and exciting work across the continents. What was an anomaly like Pilipino Food (1972) by Ed Badajos or Squeak the Mouse (1984) by Mattioli lead to a series of works like Gon by Masashi Tanaka and the Frank series by Jim Woodring in the 1990s, in addition to single works by a variety of artists like Mea Culpa by Peter Kalberkamp and The Silent City by Erez Yakin.[9]

Forecasting this rise in wordless novels was L’Association, a noted French publisher of bande dessinée, when it published Comix 2000 in celebration of the millennium. This was a mammoth book of 2000 pages of wordless comics by 324 artists from 29 different countries and it became a reference to many artists who would go on to create wordless novels.

What was once only practiced by a few artists slowly began attracting others like Eric Drooker, Thomas Ott, and Chris Lanier, whose scratchboard drawings imitate the appearance of a woodcut. These and other artists committed to the wordless novel have strengthened the foundation for a growing assortment that extends today in the work of Andrzej Klimowski, Vincent Fortemps, Michael Matthys, Winshluss, Marc-Antoine Mathieu, Danijel Žeželj and numerous others.

Not only are many of these wordless novels incredibly rich in narrative scope but the media varies as much as the themes. These novels fall within the scope of comics, but there are also choice children’s picture books that have the same sense of excitement and urgency associated with graphic novels that cross back and forth between the two audiences. A good example of this crossover is Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, which won many awards including both the Angouleme International Comics Festival Prize for Best Album and the New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books award.

Marshall Gregory in his recent book, Shaped by Stories: The Ethical Power of Narratives, writes: ‘We find stories useful because they swallow the whole world, and in fact the domain of stories may be the only form of human learning other than religion that makes the attempt to encompass the entirety of human life and experience.’ (31) This was true with the woodcut novel and continues today with the wordless graphic novel; they attest to the power of stories to display the mystery of our lives.

Works Cited

Gregory, Marshall W. Shaped by Stories: The Ethical Power of Narratives. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame, 2009.

Johnston, Rosemary R. ‘Graphic Trinities: Languages, Literature, and Words-in-Pictures in Shaun Tan’s The Arrival.’ Visual Communication 11.4 (2012): 421-41.

Lutes, Jason. Berlin: City of Stones. Book One. Montreal, Quebec: Drawn & Quarterly, 2001.

Nodelman, Perry. Words about Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books. Athens: University of Georgia, 1988.

Wolff, Kurt, and Michael Ermarth (ed). Kurt Wolff: A Portrait in Essays & Letters. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1991.

David A. Beronä is a historian of the woodcut novel and wordless comics. He is the author of Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels (2008)—with editions in French and Korean, a winner at the New York Book Show, and a Harvey Awards nominee. He has published and presented papers widely on these topics with essays in Critical Approaches to Comics: Theory and Methods (Routledge, 2011) and The Language of Comics: Word and Image (University Press of Mississippi, 2001). He recently selected and edited Alastair Drawings and Illustrations (Dover Publications, 2011) and Eric Gill’s Masterpieces of Wood Engraving (Dover Publications, 2013). He is a member of the visiting faculty at the Center for Cartoon Studies and the Dean of the Library and Academic Support Services at Plymouth State University, New Hampshire.

[1] – It is important to note in the history of publishing that Wolff left Germany in 1930 and immigrated to New York. In 1942 he founded Pantheon Books and published the wordless novel Danse Macabre by Masereel in the same year. Pantheon Books has continued this commitment to graphic artists and championed graphic novels by Art Spiegelman, Marjane Satrapi, and others in recent years.

[2] – Although Nodelman’s focus is on children’s picture books, I have found that his evaluation of reading a wordless book also aptly applies to wordless comics.

[3] – There is a growing list of contemporary artists who have published a woodcut novel including Marta Chudolinska, Stefan Berg, Megan Speer, and Neil Bousfield. Chudolinska’s woodcut novel Back + Forth was a finalist in the Best Book category of the 2010 Doug Wright Awards.

[4] – Cohen makes a close association between the woodcut novel and comics when he acknowledges in reference to Passionate Journey that the “cartoonlike flavor of the ending is a characteristic Masereel would repeat again and again in his woodcut novels.”

[5] – There is disagreement when the term “graphic novel,” first originated. Kyle and Wheary published a book length comic Beyond Time and Again: a graphic novel by George Metzger in 1976, which was two years prior to Eisner’s publication of A Contract With God. For further discussion, see: http://www.oocities.org/rucervine/002261.html

[6] – Tom Inge was instrumental in comic scholarship as he indicates in this email:

“I set up the first panel on comics held at the third meeting of the new Popular Culture Association in Indianapolis, Indiana, in April 1973. I brought together a group of friends to talk about comics as literature, art, and drama (Maurice Duke, Morris Yarowsky, and John Lyle), and somewhere in the files of the association at Bowling Green is a set of their papers. In the first few years of the association conferences, we distributed copies of the papers rather than read them.

The first panel on comics to be held at a meeting of the Modern Language Association was in New York in December of 1978. Under the auspices of the American Humor Studies Association, which I had just helped start, I held a panel on the topic ‘What’s So Funny About the Comics?’ My speakers were Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman. Will had just published A CONTRACT WITH GOD (he had allowed me to read the pencil rough the year before while I was visiting with him in White Plains) and Art was drawing the early chapters of MAUS for RAW magazine. Francoise Mouly came along for the discussion. Unfortunately I did not tape record what they said or keep notes. It has taken the MLA over thirty some years to establish a permanent discussion group devoted to the graphic novel.

(Inge, M. Thomas. “PCA Question.” Email to Nicole Freim and Amy K. Nyberg. 28 June, 2011.)

[7] – David Wiesner Caldecott Medal Acceptance Speech 1991 for Tuesday,”Why Frogs? Why Tuesday?” pays tribute to his discovery of Lynd Ward’s woodcut novel, Madman’s Drum that “became a catalyst for many of my own visual ideas.”

[8] – I sent a copy of one of my earlier articles on woodcut novels to Will Eisner and asked if he was familiar with the work of these earlier pioneers. He replied in a letter dated August 7, 1995, “Thank you for the article from Bookman’s Weekly. I found it so pertinent that I am referring to it in Graphic Storytelling. I share with you your admiration for Lynd Ward and the breed of wood engraving artists who cut the path to the modern graphic novel.”

[9] – For an extended list of wordless comics compiled by Mike Rhode, Tom Furtwangler, and David Wybenga see: “Stories Without Words: A Bibliography with Annotations.”

Mike Rhode

2013/05/23 at 14:20

A copy of the Stories Without Words bibliography may be purchased via http://www.lulu.com/shop/michael-rhode/stories-without-words-a-bibliography-with-annotations-2008-edition/paperback/product-4268891.html

LikeLike