Verisimilitude and (The Act of) Reading

by Yiru Lim

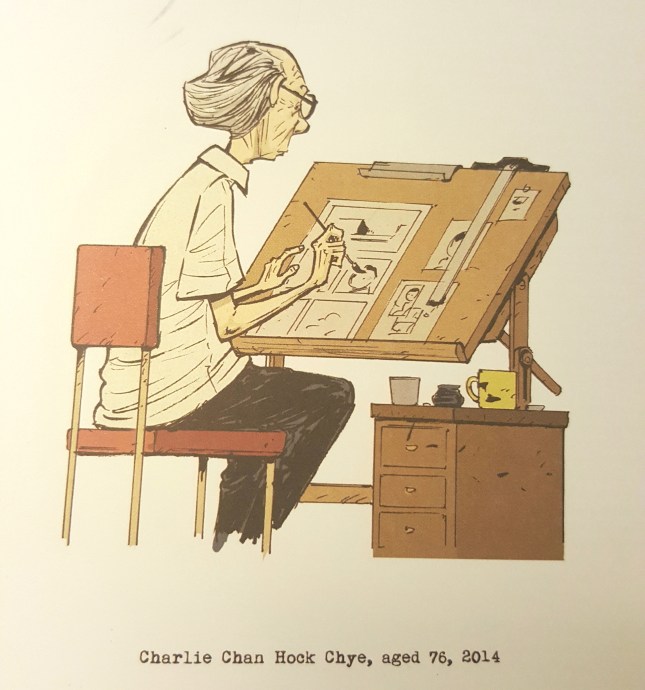

Figure 1

Source: The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, p. 307. Copyright © 2015 by Sonny Liew. Published in Singapore by Epigram Books http://www.epigrambooks.sg

Singapore’s official version of history is primarily enshrined in the memoirs of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first Prime Minister. Titled The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew, the memoirs were originally published in two volumes in 1998 and 2000 and a memorial edition was released by Marshall Cavendish in 2015, the year of Mr Lee’s passing. Revisionist accounts that stand in opposition to this seminal publication attempt to fill what they see as a void in Singapore’s history: the voice of the opposition, especially in the narratives concerning nation building and independence. They exist in a myriad of forms and genres—film, scholarly publications, prose, poetry—and they seek to debunk existing narratives and proffer more balanced perspectives of history.

Some recent examples include academic publications like Comet in Our Sky (2015), that speaks of the alleged communist Lim Chin Siong and his role in securing Singapore’s independence; Tan Pin Pin’s documentary film To Singapore, With Love (2013); Jeremy Tiang’s State of Emergency: A Novel (2017); and Sonny Liew’s graphic novel The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (2015). Tan’s film has been banned from being screened in Singapore while the latter two have had their grants revoked by the National Arts Council of Singapore (NAC) (Ho, 2017, Today Online 2015 & 2014). Although Liew’s graphic novel did not receive government approval, it has taken the literary world by storm. It became the first graphic novel to win the Singapore Literature Prize in 2016 and has garnered Liew six Eisner nominations and three Eisner Awards this year (Martin, 2017).

However, what really sets Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (2015) apart from earlier publications or film releases is not the number of awards received, but rather the extended study of the making of history within the text. Although its sympathies lie with views that run counter to those of the government, the graphic novel’s treatment of history and its many narratives problematizes how historical narratives are constructed and understood and tries not to privilege one narrative over the other, leaving the work of selection to the reader. As the title of the work implies, its method lies in the laying bare of the art behind narrative construction, reception and acceptance; it becomes an “investigation of the social and ideological production of meaning” (Hutcheon 6).

The art of this text is a multi-layered construct that refers to both method and product, process and end. The art is what the readers see on the page but it also refers to the art of construction enacted by Charlie Chan (in the presentation of his life and the events of the time), Liew (in the selection and putting together of real and imagined sources) and the reader (in the understanding and constructing of Charlie Chan and the socio-political events acting upon this character).

Of prime importance in the consideration of art in this text is the use of verisimilitude. It is a quality that is frequently overlooked in any text precisely because it acts as an eraser, making the narrative transparent in the way it hides artistic decisions and moves through its realistic (re-)construction of events, story or plot. It seeks to naturalize the artificial nature of any fictional text in order to sustain the illusion of the real.

In The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, the illusion of the real is essentially borne by the use of purportedly real documents and the conventions that history, autobiography and biography rely on. These work together to create the titular character and his life, supplying the mirage of authenticity perceived by the reader. For example, the reader looks at photographs of Charlie when he was young, flips through pages that claim to show news clippings in his old notebooks or portraits he has done of himself or of family members and reads comic texts that Charlie created. Interspersed among these is archival material: referendum day information flyers, photographs of politicians and posters for the different campaigns and movements in Singapore over the years.

It is not surprising, then, that many readers have thought Charlie Chan to be a real person who has lived through the events he narrates. The trappings of reality they witness become the evidence by which they judge Charlie and history. By making the reader determine the validity of the information presented within the text, the graphic novel sets out to test the limits of representation in terms of how we (can) know the past:

The issue of representation in both fiction and history has usually been dealt with in epistemological terms, in terms of how we know the past. […] We only have access to the past today through its traces – its documents, the testimony of witnesses, and other archival materials. In other words, we only have representations of the past from which to construct our narratives or explanations. […] The representation of history becomes the history of representation. What this means is that postmodern art acknowledges and accepts the challenge of tradition: the history of representation cannot be escaped but it can be both exploited and commented on critically through irony and parody (Hutcheon 55).

As Linda Hutcheon explains in the quote above, representation allows us to know the past but it can also betray, deceive and undermine understanding. An unquestioning acceptance of representation on the part of many readers is exploited in order to expose the epistemological concerns behind how we know and accept narratives, especially those of historical import. As such, when readers realise that Charlie Chan is not real but a fictional character, their appraisal and understanding of (historical) meaning undergo a change. The narrative of history—that mask of the real embodied by Charlie’s life and the events that he lives through—has to be renegotiated.

This overt engagement with representation is enacted not only at the level of reading but also embodied by the many styles that Liew incorporates within the text. These styles serve to signal the history of representation that is integral to an understanding of how we represent history itself. By flaunting the style in which content is presented and re-presented, the text emphasises the artifice of the endeavour, which undermines representation, calling it into question. It is in this way that the artful putting together of the real and the artificial becomes the raison d’être of the graphic novel: to put together is also to pull apart.

Thus, the information within the text that had been accepted as real must now be re-evaluated with a critical lens. Familiar tools that usually signify veracity are now suspect, playing with the readers’ notions of reality and hence history. Familiar conventions like using dates, archival information and material; stating ages, places and times; and using supporting scholarly research can serve to transmit truth—a contentious concept in itself—but is shown to also be as likely to serve ideological and social purposes that are frequently biased in presentation. Take, for example, classic examples of ‘evidence’ like the photograph. All the photographs featured in the text are real in the sense that they exist. However, the purposes for which they are used underscore how turning to archival material to verify historical truth cannot be taken for granted.

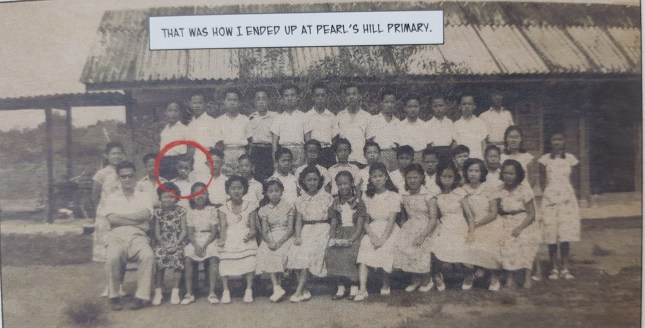

In figures 2 and 3, photographs are used to rationalise Charlie Chan’s existence by appealing to the common logic of verifying meaning through evidence. In figure 2, Charlie Chan is identified as the child whose face is circled in red. In figure 3, a photograph retrieved from the National Archives of Singapore is re-presented as having been pasted in one of Charlie’s old notebooks (note the replication of sticky tape along the sides of the photograph).

Figure 2

Source: The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, p. 18. Copyright © 2015 by Sonny Liew. Published in Singapore by Epigram Books http://www.epigrambooks.sg

Figure 3

Source: The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, p. 173. Copyright © 2015 by Sonny Liew. Published in Singapore by Epigram Books http://www.epigrambooks.sg

The images and words (e.g. “Pearl’s Hill Primary”[1] and the caption under the photograph in figure 3) may seem real and hence encourage readers to look past them, creating the transparency of verisimilitude within the text. The words and images serve to erase themselves in understanding and to instead translate into tangible reality, that is, in the creation of a life, a being, that stands apart from the reader as real and as apprehensible in time and space. The erasure of language—or other tools that labour under verisimilitude—is effected because readers see them merely as a means to an end. They serve to convey meaning or to transmit a message, they are unimportant in themselves. However this is merely a duplicitous act on the part of the author. It is a lie that is as yet uncovered by the reader who believes in the actual existence of Charlie Chan and all the attendant trappings of reality that go along with the creation of a life.

The reliance on and incorporation of dates, hand-written or hand-drawn material, artefacts and archival information, even scholarly comment within the margins and in the extensive notes at the end of the graphic novel, work to create the artifice, making the transparency of verisimilitude the true opaque object to be reckoned with within the text. It is not a specific narrative that needs to be refuted; it is a method of reading that needs to be refined/redefined. The true subject matter of the graphic novel is not the specific history of a nation-state or certain political or historical persons. What The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye really grapples with is the nature of representation and what that entails when one tries to understand history and one’s place in it.

When the artifice is realised, the words and images lose their transparency, causing them to become necessary obstacles in the way of understanding rather than well-oiled rollers in subservience only to the story. Consequently—and because so many of our narratives rely on verisimilitude and its tools for easy acceptance—the nature of representation becomes an uneasy reality that one must acknowledge in every reading of every narrative.

This making opaque of verisimilitude in this text is akin to what Paul Valéry sees as the distinction between abstract thought and poetry. Valéry contends that since poetry is an “art of language,” distinguishing between the practical and poetic aspects and functions of said language is important (64). For him, the primary distinction lies in the way in which language disappears in practical use. Like (uninspected) verisimilitude, language disappears when understanding happens. The utterance or sentence on the page is discarded when the recipient/reader understands the message. The understood message can be transmitted in other ways and forms, but the message remains. What poetry does to language is to make it bear repetition because of its refusal to disappear. Language “asserts itself” and “outlives understanding,” making it endure (Valéry 65). The repetition poetic that language bears endows it with plurality, makes it resistant to unitary interpretations. This change in language, when it is put to poetic uses, is what happens to verisimilitude when it is made the subject of representation. No longer able to disappear, verisimilitude is not the vehicle of the message but the message itself. As such, how we read and how we derive meaning become the subjects of the reader’s quest in the text. One does not ask if history is; one asks how and why history is. We not only appreciate the complexities behind representation but also see how we play into such conventions.

So who is Charlie Chan Hock Chye? He is the man we look past to look into, so that we may ourselves be read.

Yiru Lim is a lecturer at the Singapore University of Social Sciences and she specializes in twentieth century and contemporary English literature. Her research interests lie in narrative, the novel, and the coming together of visual and literary art.

References

Ho, Olivia. “Jeremy Tiang completed debut novel without full grant from NAC.” The Straits Times. 27 Jun 2017. www.straitstimes.com/lifestyle/arts/author-completed-novel-without-full-grant. Accessed 14 Sep 2017.

Hutcheon, Linda. The Politics of Postmodernism. Routledge, 2002.

Lee, Kuan Yew. The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Vol 1. Simon & Schuster, 1998.

—. The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Vol 2. Federal Publications, 2000.

—. The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. [Memorial Edition] Marshall Cavendish, 2015.

Liew, Sonny. The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Epigram, 2015.

Martin, Mayo. “Eisner Awards 2017: Graphic novelist Sonny Liew becomes first Singaporean to win at ‘Oscars of comics’” 22 Jul 2017. www.channelnewsasia.com/news/lifestyle/eisner-awards-2017-graphic-novelist-sonny-liew-becomes-first-9051868. Accessed 14 Sep 2017.

“NAC withdraws grant for graphic novel publisher due to ‘sensitive content’” Today Online. 29 May 2015. www.todayonline.com/singapore/national-arts-council-revokes-grant-for-graphic-novel-Sonny-Liew. Accessed 14 Sep 2017.

Tan, Jing Quee and Jomo K. S. (Eds.) Comet in Our Sky: Lim Chin Siong in History. SIRD & Pusat Sejarah Rakyat, 2015.

“Tan Pin Pin fails in appeal against To Singapore, with Love classification” Today Online. 12 Nov 2014. www.todayonline.com/singapore/tan-pin-pin-fails-appeal-against-singapore-love-classification. Accessed 14 Sep 2017.

Tiang, Jeremy. State of Emergency: A Novel. Epigram, 2017.

To Singapore, With Love. Dir. Tan Pin Pin. 2013.

Valéry, Paul. The Art of Poetry. Translated by Denise Folliot. Princeton U.P., 1989.

[1] Pearl’s Hill Primary was a school that the colonial government set up in Singapore in 1876.