The comic market in the Western world today is heterogeneous and complex. However, I suggest it can be divided into three main segments, or groups of readers (see also the American market commentaries Alexander 2014, Alverson 2013): the first segment are manga fans, many of which also like anime and other kinds of Japanese pop culture. The second segment are comic fans in a narrower sense, who, at least in America, read mostly superhero comic books, and other comics from the genres of science fiction and fantasy. These are the ‘fanboys and true believers’ that Matthew J. Pustz writes about in his book Comic Book Culture (Pustz 1999). Finally, the third segment is the general public. These readers are not fans, but only casual readers of comics – mostly so-called “graphic novels”, newspaper strips and collections thereof, and the occasional bestseller such as the latest Asterix album.

If we go back to the 1980s, the Western comic market was structured differently, as there were hardly any manga fans. However, back then, some manga titles were already being translated into European languages and distributed in Western countries. Who were the readers of those early manga translations? It seems likely that these were read by either or both of the other two segments which were already there in the 1980s, the comic fans and the general public.

Indeed, looking at the manga translated in the 1980s, we can distinguish between two types: those titles that were more likely to be read by comic fans, and those more popular with the general public. This distinction is not clear-cut, of course. The first type comprises of science fiction manga – e.g. Akira (Ōtomo 1988-1995), Mai the Psychic Girl (Kudō and Ikegami 1987-1988) – and samurai or ninja manga set in medieval Japan – e.g. The Legend of Kamui (Shirato 1987-1988), Lone Wolf and Cub (Koike and Kojima 1987-1991). The second type consists of manga such as the wartime stories by Keiji Nakazawa (Barefoot Gen and I Saw It, Nakazawa 1980, 1982a, 1982b), a biography of the German poet Heinrich Heine (Heine in Japan, Kita and Ogata 1988), and an introduction to economics (Japan, Inc., Ishinomori 1988, Ishinomori 1989). I hesitate to label these types “fiction” and “non-fiction”, as on the one hand Japan Inc. is mainly fictional and Barefoot Gen is a fictionalised autobiography, and on the other hand some readers of Lone Wolf and Cub have stated that part of its appeal is the factual information about medieval Japan that it conveys – e.g. fanzine reviewer Martin Skidmore: ‘this gradual education to the ancient Japanese way of thinking is, for me at least, another big attraction to the series’ (Skidmore 1988). Let us now take a closer look at one manga from each of these types.

Lone Wolf and Cub by Kazuo Koike and Gōseki Kojima was originally published as 子連れ狼 (Kozure Ōkami) in Weekly Manga Action from 1970–1976. This classic gekiga manga was very successful in Japan and was adapted into several films. In over 8000 pages, it tells the story of samurai Ittō Ogami who is accused of treason by a rival ninja clan. His wife is murdered and he flees with his infant son Daigorō and travels through medieval Japan as an assassin-for-hire.

The first English-language edition of Lone Wolf and Cub was published by the company First Comics, or First Publishing. First Comics was founded in 1983 and tried to find a niche in the American Direct Market. The format of the Lone Wolf and Cub issues published by First was similar to the standard American comic book – 16.8 by 26.1 cm – but was square bound to accommodate a higher number of pages (ca. 60). 45 of these issues were published monthly from 1987 until 1991, which means that about two thirds of the series were left unpublished. Publication ceased when First went bankrupt. It is unclear whether this bankruptcy was due to an increasing cover price for Lone Wolf and Cub (from $1.95 for the first issues to $3.25 for the final issues) and consequently declining sales (Dimalanta 2011), or whether it was due to general financial problems at the company which were unrelated to Lone Wolf and Cub.

A distinctive feature of this edition was the cover images, which for the first few issues were drawn by Frank Miller and Lynn Varley. Frank Miller also provided introductions to these issues, which indicates how important the endorsement of a popular American comics author must have been for American comic fans. Perhaps the most interesting of these introductions is the one for issue #3 from July 1987. In it, Miller uses the word ‘manga’ and explains what manga are: ‘They sell millions of copies to Japanese of all ages and both sexes, and offer an astonishing diversity in subject matter.’ – as opposed to US comics, one is tempted to add. Miller goes on: ‘This segment, in particular, has as its focal point the premeditated murder of a priest. Since the priest is Buddhist, not Christian, it’s not likely to draw fire from our right-wing evangelists, but pro-censorship liberals are sure to find it morally and politically incorrect, just as they are certainly not going to read it deeply enough or carefully enough to understand its profoundly Buddhist philosophical underpinnings.’ This sounds almost as if Miller, who at that time was also involved in a debate around rating systems and censorship in comics (The Comics Journal 1987), was talking about his own experiences in the US comic industry.

It is also interesting to read the letter pages in Lone Wolf and Cub, which started in issue #6 from October 1987. Of course, we have to be careful when analysing letters to the editor printed in comic books, as they are known to have been carefully selected, if not forged entirely. At best, letters tell us what the editors want the readers to think that the other readers think. Still, the letters in Lone Wolf and Cub reveal a close affiliation with comic book fandom. In the aforementioned issue, a reader named Walter M.B. Spiro says: ‘The last couple of years have been exciting one[s] for comic collectors like myself. After suffering through the 70s it is a joy to look forward to that next issue of not just one but numerous titles.’ Another reader, who calls himself Paladin, writes: ‘The idea of a kid with the assassin is intriguing… much like it must have been when Robin was first introduced in Batman’. A reader named C. Coleman simply says: ‘I am a follower of the genius, Frank Miller.’

Lone Wolf and Cub also made it to the front page of the Comics Buyer’s Guide #708 in June 12, 1987. A short article with the headline ‘First sells out “Cub” edition #2’ reports that the first issue of Lone Wolf and Cub had sold out not only in its first but also in its second printing, and went into a third printing. The combined sales of those two first printings were 110,000 copies, which at that time was not an extraordinarily high number. However, this CBG article shows that the comic book industry was watching closely how Lone Wolf and Cub was performing on the market.

Several comic magazines and fanzines reviewed Lone Wolf and Cub when it first came out. In one of them, the British fanzine FA, formerly Fantasy Advertiser, Martin Skidmore writes: ‘At last, in the last year or two, a few Japanese comics have made it into the English language. Maybe you’ve read Marvel’s Akira, or one of Eclipse’s titles – Mai, Kamui or Area 88 – or even the subject of this article.’ (Skidmore 1988)

Here Skidmore mentions other manga published in the US, which probably would not have been possible in the Lone Wolf and Cub letter pages, and links them together on the basis of their Japanese origin. However, Skidmore continues: ‘So, with a little interest developing in Japanese comics, largely due to Frederik Schodt’s magnificent, invaluable Manga! Manga! as well as the Miller connection, it was inevitable that American publishers would become aware of the huge, rich, diverse collection of material, and want to translate some of it.’ Here, too, Frank Miller is seen as an important link between manga and US comic fandom.

Even a mainstream newspaper mentioned Lone Wolf and Cub once. The Pittsburgh Press from January 13, 1988, ran an article in their finance section with the headline ‘Comic book collecting a serious investment’. The article starts like this: ‘Here’s an investment that is slower than a speeding bullet but might in time bring super returns and pay your kid’s college tuition. Collect comics – Superman, Archie, the new Japanese import Lone Wolf and Cub, or any of hundreds of others both old and new.’ Here, Lone Wolf and Cub is lumped together with original American comics like Superman and Archie. It is only recommended as an investment, not for reading. Its content, quality and “sJapaneseness” do not matter much here (even though it is characterised as a ‘Japanese import’), and no connection to other manga is made.

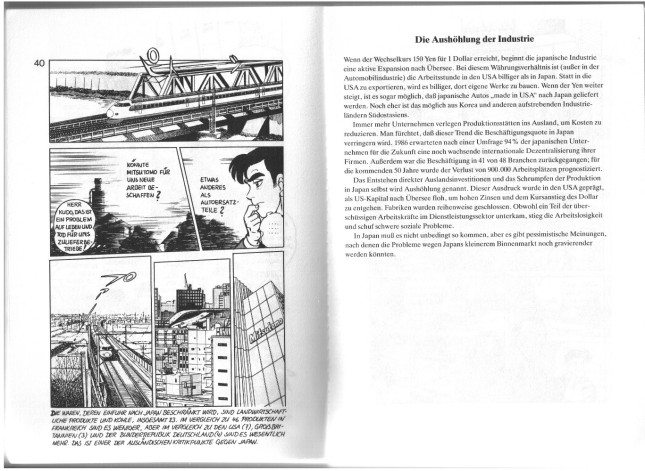

Let us now move on to an example of the second kind of manga, those translated for the general public. Japan Inc. by Shōtarō Ishinomori was originally published as マンガ日本経済入門 (Manga Nihon Keizai Nyūmon) in three volumes from 1986–1988. It is a fictional story about two young managers in a Japanese company which is struggling with various economic problems. This comic is interspersed with occasional text sections explaining economic facts and theories. It was translated into English by the University of California Press in 1988 and into French by the publishing house Albin Michel in 1989, only the latter of which could be regarded as a comics publisher.

My focus is on the German edition here, which was published as a paperback book of 20.8 by 14.7 cm under the title Japan GmbH – Eine Einführung in die japanische Wirtschaft (‘Japan Inc. – an introduction to Japanese economy’). Out of the three original volumes, only the first was translated into German. However, the fact that the German edition came out only three years after the original publication meant that it still had a certain timeliness. After all, the West was very much interested in Japanese economics in 1989, two years before the Japanese bubble economy burst. The publisher of Japan GmbH was Norman Rentrop in Bonn, who had published economics, business and management non-fiction before, but no comics. Another unusual aspect of Japan GmbH was its cover price of DM 49.80 (approximately € 25), which might have been adequate for an economics textbook, but was quite high for a 320 page black-and-white comic and thus not attractive for comic fans.

The text on the back cover of Japan GmbH (pictured below) also betrays an orientation towards businesspeople rather than comic fans: ‘Japan, for many still an unpredictable economic competitor in the Far East, has become a leader on the world market through consistent technological and economic development. At the same time, the sons of the samurai have developed an economic structure and a way of thinking that is inscrutable for Europeans and Americans. However, insight into the Japanese economy is essential, as Japan is also an interesting sales market’ (my translation).

The introduction to Japan GmbH takes a similar direction. Peter Odrich, a journalist and an expert on economics and Asia, starts by explaining what manga are and what significance they have in Japan, but he then goes on to interpret the content of Japan GmbH in the context of the significance of economics in Japanese society.

Japan GmbH had significantly less impact on the German-language comics scene than Lone Wolf and Cub on the English-language scene. One of the most important German comics magazines of the late 1980s and early 1990s was Rraah!, which was founded in 1987. Therefore, it was already established when Japan GmbH was published in 1989 and could have reviewed it. However, Japan GmbH was not even mentioned in Rraah! until 1994, in an overview article of all manga available in German at that time (“Mangas auf Deutsch” 1994, 25). However, the coverage of the German-language comics market was generally exhaustive in Rraah!. Even the first German translation of Lone Wolf and Cub (Koike and Kojima 1989), which appeared in an issue of a rather obscure comic anthology magazine named Macao, can be said to have received more attention, as it was briefly reviewed in Rraah! (Rraah! 1989, 30). This is another sign that Japan GmbH was largely ignored by the comics scene.

Interestingly, Japan GmbH was mentioned in the mainstream news magazine Der Spiegel (“Boss beim Sado” 1987). The article is from 1987, which means that it does not refer to the German translation, which was not published until two years later, but to the original Japanese edition. The title of the article, ‘Boss beim Sado’, alludes to a relatively insignificant scene in the manga in which a manager has sadomasochistic sex with a prostitute. This angle makes this article part of an ongoing tendency in the media to portray the Japanese as sexually deviant, not unlike the recent initial media coverage of an alleged Japanese “eyeball licking” fetish trend (Hornyak 2013). Thus the Spiegel article is a sensationalist news item rather than a balanced review of Japan GmbH.

To conclude, this comparison of the first English edition of Lone Wolf and Cub and the German edition of Japan Inc. and their respective reception shows that some manga translations were made for and read by comic fans, whereas others were made for and read by the general public. It seems likely that the first generation of manga fandom grew out of the former group, the comic fans. Looking at the following growth of the Western manga market, the successes of the late 1980s were dwarfed in comparison with the hit series of the 90s (Dragon Ball, Sailor Moon), and even more so later in the early 2000s (Naruto, One Piece, Bleach – cf. Alverson 2013), but these titles had the advantage of falling on fertile ground, as a manga fandom had already been established. Perhaps the necessary factor for manga readers to develop into manga fans was the devotion of comic fans to the medium. Consequently, to this day, some people say that Lone Wolf and Cub is the manga title that has ‘kicked into overdrive the manga craze in the United States’ (Voger 2006, 40).

Works Cited

Alexander, Jed. 2014. “The Future of Comics: A Casual Readership.” Jed Alexander, January 22. Accessed April 10, 2014. http://jedalexander.blogspot.de/2014/01/the-future-of-comics-casual-readership.html

Alverson, Brigid. 2013. “Manga 2013: A Smaller, More Sustainable Market.” Publishers Weekly, April 5. Accessed April 10, 2014. http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/booknews/comics/article/56693-manga-2013-a-smaller-more-sustainable-market.html

“Boss beim Sado.” 1987. Der Spiegel 31 [July 27]: 111. Accessed April 1, 2014. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13525459.html.

Dimalanta, Zedric. 2011. “A Look Back on Lone Wolf and Cub.” The Comixverse (Leaving Proof 34), July 8. Accessed April 1, 2014. http://thecomixverse.com/2011/07/08/leaving-proof-34-walking-the-assassins-road-a-look-back-on-lone-wolf-and-cub/.

“First Sells Out ‘Cub’ Edition #2.” 1987. Comic Buyer’s Guide 708:1, June 12.

Hornyak, Tim. 2013. “Blind spot: How a hoax about eye licking went global.” CNET, August 8. Accessed April 10, 2014. http://www.cnet.com/news/blind-spot-how-a-hoax-about-eye-licking-went-global/

Ishinomori, Shōtarō. 1989. Japan GmbH. Eine Einführung in die japanische Wirtschaft. Bonn: Rentrop.

Ishinomori, Shōtarō. 1988. Japan Inc. An Introduction to Japanese Economics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kita, Kyōta and Keiko Ogata. 1988. Heine in Japan. Ein ‘Dichter der Liebe und Revolution.’ Düsseldorf: Verlag der Goethe-Buchhandlung.

Koike, Kazuo and Gōseki Kojima. 1987-1991. Lone Wolf and Cub. Chicago: First Comics.

Koike, Kazuo and Gōseki Kojima. 1989. “Der Wolf und sein Junges.” Macao 5.

Kudō, Kazuya and Ryōichi Ikegami. 1987-1988. Mai, the Psychic Girl. Forestville: Eclipse / San Francisco: Viz.

“Mangas auf Deutsch.” 1994. Rraah! 28:25-26, August.

Metz, Robert. 1988. “Comic Book Collecting a Serious Investment.” The Pittsburgh Press 104(200): B7, January 13. Accessed April 1, 2014. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=oHQdAAAAIBAJ&sjid=RWMEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6210%2C4807103.

Nakazawa, Keiji. 1980-1981. Gen of Hiroshima. San Francisco: Educomics.

Nakazawa, Keiji. 1982a. Barfuß durch Hiroshima. Eine Bildergeschichte gegen den Krieg. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Nakazawa, Keiji. 1982b. I Saw It. The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima. San Francisco: Educomics.

Ōtomo, Katsuhiro. 1988-1995. Akira. New York: Epic.

Pustz, Matthew J. 1999. Comic Book Culture. Fanboys and True Believers. (Studies in popular culture.) Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Rraah! 8, August 1989.

Shirato, Sanpei. 1987-1988. The Legend of Kamui. Forestville: Eclipse / San Francisco: Viz.

Skidmore, Martin. 1989. “Overview: Lone Wolf and Cub. The First Eleven Issues.” FA – the Comiczine 104, July. Acessed March 31, 2014. http://comiczine-fa.com/?p=3905.

The Comics Journal 118, December 1987.

Voger, Mark. 2006. The Dark Age. Grim, Great & Gimmicky Post-Modern Comics. Raleigh: TwoMorrows. Accessed April 1, 2014. http://books.google.de/books?id=5IYEoDPztHEC.

Martin de la Iglesia studied Art History and Library and Information Science at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. In 2007 he wrote his Master’s Thesis in London on the reception of US comics in the United Kingdom. Currently he is a PhD student at Heidelberg University (dissertation topic: the early reception of manga in the West). At the same time he works as a librarian in Göttingen, Germany. His research interests include comics, art geography, reception history and aesthetics, and art historical methodology. All of his publications are available as Open Access. He blogs at http://650centplague.wordpress.com/

Stephan Packard

2014/07/15 at 08:49

Thanks for a great and insightful article!

On your oriiginal division of the Western market into 3 groups, I wonder where you’d put avantgarde and auteur comics? Where do the people go that read Gillen’s Three”, Fraction’s “Sex Criminals”, or anythgin by Mattotti?

LikeLike

Martin de la Iglesia

2014/07/15 at 20:25

Thank you for reading it!

As for avantgarde and auteur comics: according to Matthew Pustz, comic book culture is divided into ‘mainstream’ and ‘alternative’ readers, and I guess it’s mainly the latter who also read avantgarde and auteur comics (albeit not only in comic book form) – i.e. a sub-segment of comic fandom. That being said, I don’t see avantgarde comics having that much of an impact on the comics market to warrant their consideration in the rather coarse three-part division described above.

Still, it would certainly be interesting to look deeper into avantgarde comics readership, particularly with regard to early manga translations (e.g. Yoshiharu Tsuge).

LikeLike

Martin de la Iglesia

2019/05/03 at 15:32

I only now realised I have made a mistake in my reference to Martin Skidmore’s article in FA: issue 104 was published in 1988, not 1989.

LikeLike